The Demand of Intellectual Property Management for Taiwanese Enterprises

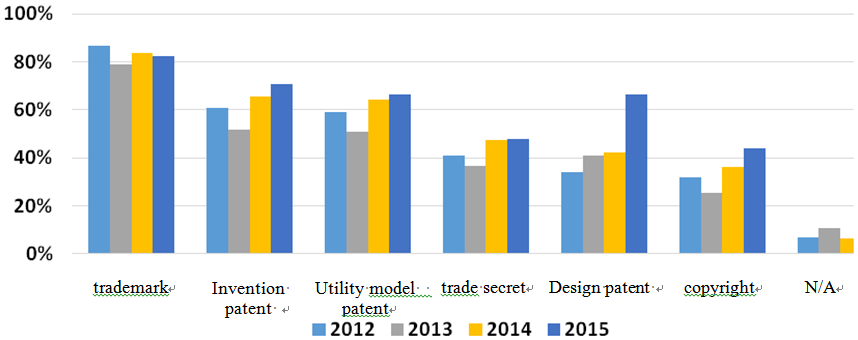

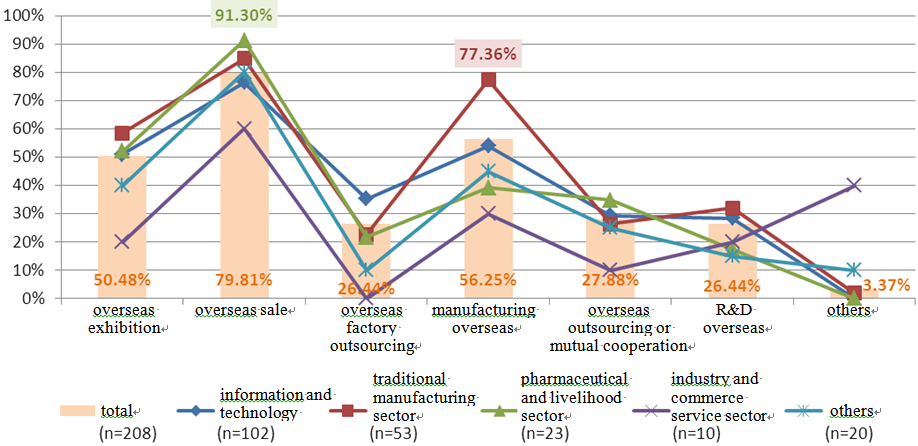

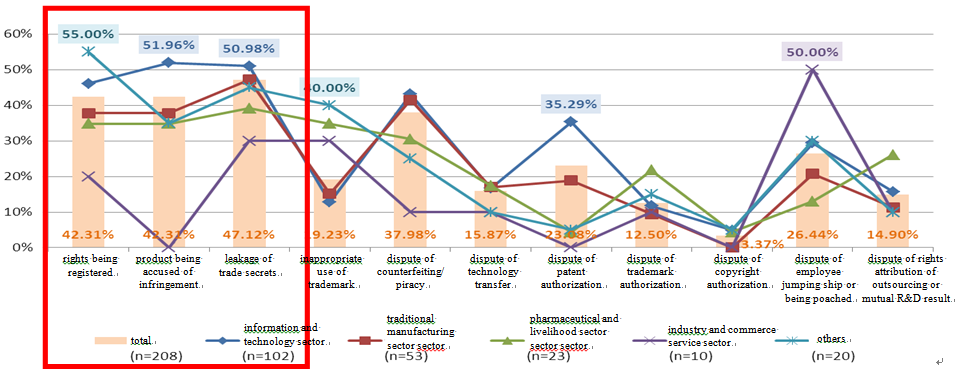

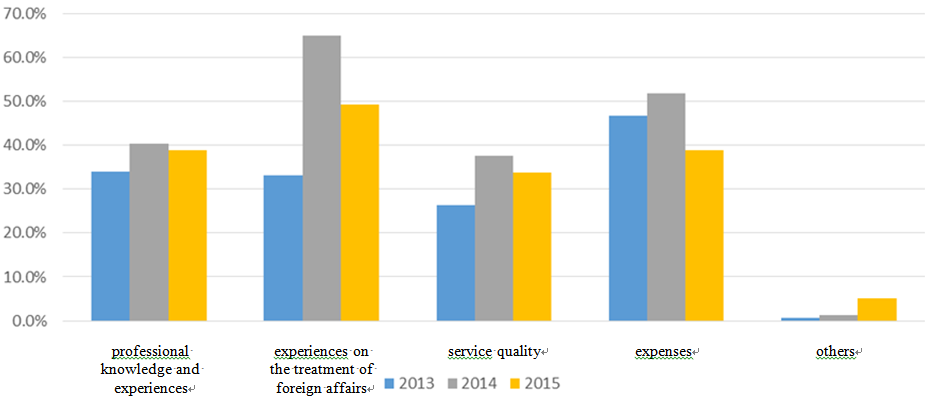

Science & Technology Law Institute (STLI), Institute for Information Industry has conducted the survey of “The current status and demand of intellectual property management for Taiwanese enterprises” to listed companies for consecutive four years since 2012. Based on the survey result, three trends of intellectual property management for Taiwanese enterprises have been found and four recommendations have been proposed with detail descriptions as below.

Antitrust Issue of Reasonable Royalty and Prohibition of Excessive Pricing in Taiwan A proposed antitrust framework to determine a reasonable royalty I. INTRODUCTION “Can, and should antitrust laws and authorities step in market prices?” - It has long been a controversial antitrust issue, especially when an antitrust case is involved with allegedly unlawful monopolization (or called abuse of monopoly in some countries), Intellectual Property (IP) rights (IPRs), reasonable royalties, and the complex and fast-changing technologies behind. It thus constitutes the tricky and challenging antitrust issue of reasonable royalty - “if a monopolistic firm is charging reasonable royalties or abusing its monopoly power?” Since the goals and regimes of antitrust are very different between Asia, the United States (the U.S.), and Europe, there are consequently various ways to deal with such issue. A. China and its Per-Se Violation of Excessive Pricing Several countries in East Asia aim to protect fair competition and social public interests via antitrust laws, including some other non-competition-based goals.[1] China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan’s goals of antitrust all include protection of fair competition. China also articulates its goals to maintain public interests and promote socialist market economy. Japan also aims to promote the employment rate and the level of national income which are not competition-based goals. Furthermore, South Korea expresses its antitrust goal to achieve balanced economic development which is somehow tricky to judge. As a result of the concepts of fairness and non-competition interests, the antitrust issue of reasonable royalty can possibly lead to the determination of unfairly high prices and thus constitutes an unlawful per se violation of excessive pricing in East Asia. Take China as an example, China explicitly articulates the prohibition of charging unfairly high prices as a firm in dominant position.[2] Moreover, China has further stepped in determining “appropriate royalties” supposedly charged by licensors and has demanded foreign firms in China to charge lower royalty rates.[3] In Huawei v. InterDigital Technology Corporation (IDC), the court ruled that IDC charged Chinese firms unfairly high royalties and further held that the royalty rates of the Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) charged by IDC shall not exceed 0.019%. In the Qualcomm case in China, National Development and Reform Commission of China ruled that Qualcomm was charging unfairly high prices and demanded it to lower its royalty base. Additionally, China’s Anti-Monopoly Guidelines on the Abuse of Intellectual Property Rights published by the Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China (MOFCOM) in March of 2017 were passed in the end of 2018.[4] While already waiting to be formally executed, these Guidelines had received comments regarding reasonable royalties – especially the antitrust violation of licensing IPRs at unfairly high prices with 5 listed factors to consider whether there is abuse of dominant position.[5] By pointing out the dangers of regulating price following with potential harms to competition, one of the comments encourages the Guidelines to have the relevant factors in terms of determining unfairly high prices, such as the prices of comparable licenses instead of any other irrelevant indicators. B. European Commission (EC)[6] and its Per-Se Violation of Excessive Pricing While embracing free market economy and achieving social and political goals at the same time, EC prohibits unfairly high prices as unlawful per se by articulating “directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase or selling prices or other unfair trading conditions” as abuse of market dominance.[7] The test to it started from the case United Brands (1978) which stipulates the difference between cost and price.[8] As the time came to the late 2000s, EC once said that “it takes no position on what a reasonable royalty is” in 2013 but later stated its option to act directly against excessive prices in 2016.[9] In 2017, the Copyright and Communication Consulting Agency/Latvian Authors Association (the AKKA/LAA case) was brought to the court for charging excessive fees for its exclusive right to license.[10] According to Article 267(a) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) shall have jurisdiction to give preliminary rulings concerning the interpretation of the Treaties. Given the questions referred to the CJEU in the AKKA/LAA case, the concept of excessive pricing therefore had the chance to be clarified further. [11] Three important principles established in this case are: (1) comparing the price at issue between the prices charged by other appropriate and sufficient comparators; (2) there is no threshold of what a royalty rate must be regarded as appreciably high, but a difference between rates must be both significant and persistent to be appreciable; (3) an analysis of fairness justification provided by the alleged dominant firm must be conducted.[12] The AKKA/LAA case reestablished and reaffirmed EC’s resolve to enforce prohibition of excessive pricing. As for the recent times, the Danish Competition Council found that the Swedish pharmaceutical distributor - CD Pharma had abused its dominant position by charging excessive prices for Syntocinon, ruling the price increase of 2000% unjustified.[13] The appeal against this decision is now pending. Many more excessive pricing cases are still ongoing within EU jurisdictions. C. The U.S. and its Hands-Off Approach towards Pricing U.S., on the other hand, never did and does not prohibit monopoly or excessive pricing, and has been warning the great dangers and potential harms to competition resulting from regulating price.[14] The long-established principle of not regulating price, however, was shaken by U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC)’s complaint against Qualcomm for conducting unfair methods of competition in 2017.[15] U.S. FTC filed a complaint against Qualcomm in 2017, alleging Qualcomm violating the Federal Trade Commission Act.According to the complaint, customers accepted elevated royalties that a court would not determine fair and reasonable due to Qualcomm’s unlawful maintenance of monopoly. However, the complaint fails to explain what a reasonable royalty is and why Qualcomm charges more than it is supposed to be charging.[16] Furthermore, the dissenting statement of this case states that the theory adopted by FTC required proof of Qualcomm charging unfairly high royalties where there was failure of proving reasonable royalty baseline in the case.[17] In January of 2019, this case finally kicked off in a California courtroom and the outcome of it will definitely have tremendous impacts on every stakeholder. Later in May 2019, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California found that Qualcomm violated the FTC Act. The case is still ongoing. D. Taiwan and its Unclear Attitude towards the Antitrust Issue of Reasonable Royalty So, where does Taiwan stand between prohibition of excessive pricing and the hands-off approach in the U.S.? In Taiwan, improperly setting, maintaining, or changing the price for goods or the remuneration for services as a monopolistic enterprise has long been unlawful per se since Taiwan’s Fair Trade Act (FTA) was enacted in 1991.[18] This unlawful per se violation is in fact Taiwan’s prohibition of excessive pricing. However, the attitudes of Taiwan Fair Trade Commission (TFTC) and the courts in Taiwan towards the antitrust issue of reasonable royalty can be switching. They have avoided the issue, left the issue for private contracting, resorted to Patent Act, and determined royalties for the involving parties. Antitrust cases involving the issue of reasonable royalty can be a matter of billion-dollar fines, tremendous costs of litigation, negative impacts on innovation and competition, and harms to consumers. Such important issue can no longer be neglected by Taiwan anymore. By focusing on the antitrust issue of reasonable royalty in Taiwan, this paper will begin with the past attitude and the current antitrust framework of reasonable royalty in Taiwan. Further, because Taiwan has been looking up to the U.S. and its patent law in terms of calculating reasonable royalty in patent infringement cases; this paper will then turn to the reasonable royalty approach in Taiwan and the U.S. respectively. Even though this paper does not support prohibition of excessive pricing, we hope the antitrust issue of reasonable royalty in any excessive pricing case in Taiwan will be properly and carefully dealt with. Therefore, based on the proposed methodologies in a 2016 paper[19], the core of this paper will be proposing a framework for Taiwan in order to give clearer directions on how to face the antitrust issue of reasonable royalty along with the potential violation of Article 9 of FTA. II. THE PAST ATTITUDE AND THE CURRENT ANTITRUST FRAMEWORK OF REASONABLE ROYALTY IN TAIWAN A. The RCA, Catrick, and Microsoft case - 1995 ~ 2003 TFTC’s attitude towards the antitrust issue of reasonable royalty had long been unclear. In TFTC v. Radio of Corporation of America (RCA)(1995), RCA settled with TFTC for the accusation of charging improper royalties.[20]In TFTC v. Microsoft (2002-2003), Microsoft settled with TFTC after 10 months being accused of conducting excessive pricing. [21] However, the details of both settlements were never published. In the Catrick case (1998), a U.S. firm named Catrick was accused of improperly charging royalties.[22] TFTC attempted to resort to Patent Act but Patent Act at that time was silent on calculation of royalties. To play safe, TFTC did not interpret FTA or determine a reasonable royalty. Instead, TFTC left the issue to be solved under the principle of freedom of contract and closed the investigation.[23] B. The CD-R Patent Pool Case – 2001~2015 1. Summary of the case Even being given 15 years of time, the antitrust issue of reasonable royalty still remained unsolved in the CD-R Patent Pool case (2001-2015). Upon the investigation from 1999, TFTC found that Philips Electronics NV (Philips) and other two companies had violated Article 10 of FTA with their unlawful concerted action and abuse of dominance in 2001.[24] Here is the background: The CD-R manufactures in Taiwan accounted for 80% of the global CD-R manufacturing output when the time the CD-R technologies were a worldwide industrial revolution. The price of CD-R was originally at around $60 per piece in 1990. It later went down to $0.20 per piece in 2000. However, the three enterprises in the case kept refusing to change the formula for calculating the license fee. Thus, the pricing issue here was that if the three monopolistic enterprises improperly maintained the formula for calculating the CD-R license fee by joint licensing and refusing to change the license fee even though the market conditions had changed drastically at that time.[25] After a series of appeals and retrials, TFTC again ruled that Philips violated Section 2 of Article 10 of FTA by abusing its dominant position and improperly maintaining the price for its jointly licensed technologies in 2015.[26] To everyone’s disappointment, TFTC again left the determination of reasonable royalty unsolved. 2. Fights over reasonable royalty between courts and TFTC The tricky thing is, administrative courts, TFTC, Intellectual Property Court of Taiwan (IP Court of Taiwan) held totally different positions in the CD-R case in terms of the antitrust pricing issue: a. Taipei High Administrative Court (2003) [27] The court reasoned that the license fees should be determined by competition and cost structure on principle. As a result, the determinants to reasonable royalties would be supply and demand in the market. b. TFTC Decision No.095045 (2006) [28] TFTC did not hold that the defendants’ pricing practice in violation of FTA. However, it stated its position in stepping in royalties - “Business value of patents varies due to maturity of technologies and market development. Therefore, patent holders should consider prices of final products, value of patents, and contributions made by licensees while determining reasonable royalties… It is inappropriate for the antitrust authority in Taiwan to step in royalties unless there is indication of illegal monopolization or cartel. “ c. Intellectual Property Court Appeal Case No.14 (2008) [29] IP Court of Taiwan incorporated the concept of fairness in its decision by saying – “courts could only adjust the royalty rates in consideration of fairness towards both parties and other relevant factors in the contract.” Further, the court also said that it was not within TFTC’s jurisdiction to determine the reasonableness of the license fee charged by Philips. d. TFTC Decision No. 098156 (2009)[30] By revealing the prices of CD-R output, shipment of CD-R, change of market conditions within 10 years, and the 60 times higher royalty revenues earned by Philips, Sony and Taiyo Yuden, TFTC found that the profits earned by the three defendants were beyond expectation and estimation. In conclusion, TFTC again held in its 2009 decision that the three defendants violated FTA by not giving opportunities to negotiate over the CD-R license fee upon the easily perceived market changes. e. Supreme Court of Taiwan, Case No.883 (2012) [31] After the long fights between courts and TFTC for 10 years, Sony and Taiyo Yuden had stopped fighting and their cases were affirmed in 2011. As for Philips, they enjoyed a huge turning point in 2012 because the Supreme Court of Taiwan abolished IP Court of Taiwan’s 2008 verdict and ruled that the governing laws of the contracts between the involving parties were Dutch laws. f. TFTC Decision No. 104027 (2015)[32] TFTC did not get defeated and reached another decision against Philips in 2015. In the reasoning, TFTC first clarified that market prices should be determined by competition and cost structure. Then it claimed to still have the role to rule that Philips had been improperly maintaining the license fee of CD-R through abuse of dominance, refusals to renegotiate and earning excessive profits. To everyone’s disappointment, TFTC still left the determination of reasonable royalty unsolved. C. TFTC v. Qualcomm Incorporated (Qualcomm) (2015 - 2018)[33] In 2017, TFTC ruled that Qualcomm violated Article 9(1) of FTA[34] by refusing to license, imposing no license no chips policy, and conducting exclusive dealing. As for the pricing issue in this case, it was argued if the license fees charged by Qualcomm were unreasonably high and if the fees should be based on value of patents instead of net prices of manufactured phones. TFTC did point out the pricing issue in its reasoning but did not say much further. Instead, TFTC commented in the decision that Qualcomm had been enjoying excessive profits and stated that license fee was a matter of freedom of contract and negotiation.[35] After a series of fights between TFTC and Qualcomm, both parties agreed to settle in August 2018.[36] The Administrative Decision No. 106094 issued by TFTC was vacated with the replacement of the settlement[37] which Qualcomm agreed to invest hundreds of millions in Taiwan and on other matters.[38] D. The Current Antitrust Framework of Reasonable Royalty in Taiwan The current antitrust framework of reasonable royalty in Taiwan in this paper is based on the latest version of Fair Trade Act of Taiwan which was amended in 2017 and the latest version of IP Guidelines of Taiwan which was amended in 2016.[39] There are three main steps in the current antitrust framework to deal with the reasonable royalty issue that suspiciously violates FTA in Taiwan. 1. Proper conducts pursuant to Intellectual Property Laws in Taiwan First, and most importantly, Article 45 of FTA excludes the application of FTA to all “proper conducts” pursuant to all IP Laws in Taiwan where TFTC does not give quite clear explanation of.[40] The reason behind such exclusion stated in the legislative rationale of Article 45 of FTA is problematic - “Copyrights, Trademarks, and Patents are monopoly rights endowed by IP laws. Therefore, FTA shall not apply to them by nature.” [41] 2. Guidelines on Technology Licensing Arrangements (IP Guidelines of Taiwan) Secondly, TFTC shall turn to review if IP Guidelines of Taiwan apply to any licensing practice in the case when it sees Article 45 of FTA not applicable.[42] IP Guidelines of Taiwan articulates a correct and fundamental principle while reviewing a technology licensing agreement – “TFTC does not presume market power resulted from owning a patent or know-how.”[43] Further, IP Guidelines of Taiwan do not articulate reasonable royalty or excessive pricing. Instead, the Guidelines make clear of the allowed and prohibited calculation methods for royalties. By recognizing the ease of calculation as efficiency, IP Guidelines of Taiwan basically allows the end product approach and the net sales approach to be applied in a technology licensing agreement as long as the licensed technology was indeed used by the licensee.[44] Notwithstanding, TFTC still has the power to find an antitrust violation upon finding of improper matters even if a licensor complies with Section C of Article 5 of IP Guidelines of Taiwan. [45] 3. Prohibited monopolistic conducts When neither Article 45 of FTA nor IP Guidelines of Taiwan applies to the case, the last step TFTC shall take towards reasonable royalty issue is to review if Section 2 of Article 9 of FTA applies - ” Monopolistic enterprises shall not engage in improperly setting, maintaining or changing the price for goods or the remuneration for services.” [46] Basically, it is the prohibition of excessive pricing in Taiwan. To be noticed, Article 9 of FTA can only be applied when there is one or more monopolistic enterprises involved. 4. Some issues under the current antitrust framework of reasonable royalty in Taiwan a. Proper conducts pursuant to all IP laws in Taiwan. Article 45 of FTA excludes the application of FTA to what so called “proper IP conducts.” Such exclusion is based on the idea that IPRs are monopoly rights – which is problematic.[47] The fact is - IPRs are exclusive rights instead of monopoly rights. IPRs do not necessarily confer monopoly power or induce more anticompetitive behaviors than other types of property. Moreover, exercising an IPR can be engaging in improper market conducts that lessens competition. In other words, what should be kept in mind is that a proper IP conduct may still possibly constitute an antitrust violation. b. The maybe-violation in IP Guidelines of Taiwan. IP Guidelines of Taiwan are basically friendly towards the end product and the net sales approaches for calculating royalties. However, Article 5 of the Guidelines still gives TFTC the power to find a “maybe” antitrust violation upon any improper matters. Such maybe violation makes the protection under IP Guidelines shaky and even not that useful. c. No such thing as excessive profit. One of the legislative reasons behind the prohibition of excessive pricing in Taiwan is that - “when a firm does not price its products based on reflection of the costs but intends to gain exorbitant profits, such improper pricing conduct would be the most effective way to exclude competition.” [48] Firstly, there is no such thing as an excessive or exorbitant profit in a free market economy when a price is determined by supply and demand which results in profits you earn accordingly. Secondly, instead of the profits, it should be the price or the pricing practice to be evaluated due to the purpose of excessive pricing violation. d. Missing harms to competition. Most important of all in any excessive pricing case – where are the harms to competition? It should be clear that unjustified profits are not what antitrust laws aim to punish but the anticompetitive market conducts that harm competition. Which is to say – if a monopolistic enterprise has been charging excessive prices through abuse of monopoly that generates harms to competition? With the ultimate goal of protecting the overall competition and consumers, there must be potential or actual harms to competition proven in any excessive pricing case. Such as higher prices, lower outputs, exclusion of competition, entry barriers, negative impact on innovation, or so. E. The Reasonable Royalty Approach under the Patent Act in Taiwan 1. Damages as reasonable royalty Article 97(1) of Patent Act of Taiwan lists three approaches for calculating damages in any event of patent infringement.[49] One of the approaches is the reasonable royalty approach.[50] The so-called reasonable royalty is the royalty the licensee would have paid if there had been a negotiation instead of an infringement. In practical, any profit earned by the licensee from the infringement is excluded from the damages while adopting such approach. Since the infringing licensee saved the costs of negotiation and the licensor spent extra costs on patent infringement litigation, it is also recognized that damages calculated by adopting the reasonable royalty approach can be more than the royalty the licensee would have paid.[51] 2. Determinants and principles in a hypothetical negotiation over royalty After all, the reasonable royalty approach assumes a hypothetical negotiation over royalty between the licensee and licensor. There are still controversies over the determinants and principles to be applied while adopting such approach. Various considerations would possibly lead to drastically different reasonable royalties just like the NT$10 million and NT$1 billion damages in the Philips v. Gigastorage case. [52] Koninklijke Philips NV (Philips) brought a patent infringement lawsuit against Gigastorage Corporation (Gigastorage, a Taiwan-based manufacturer) at the IP Court of Taiwan in 2014, alleging that Gigastorage had been infringing their Taiwanese patent from 2000 through 2015 by manufacturing and selling DVD related products. The pricing issue here is how to calculate the damages and compensation of unauthorized utilization of the patent involved where the calculation methods and considerations would make big differences. IP Court of Taiwan awarded NT$10.5 million as damages based on reasonable royalty approach in the first trial. However, the same court of different judges later ruled that the damages should be over NT$1 billion according to unjust enrichment. The case was brought to the Supreme Court of Taiwan in 2017. In September 2018, the NT$1 billion judgement was remanded and now the IP Court of Taiwan is thus responsible for a retrial.[53] Nevertheless, the two most common determinants to a reasonable royalty under this approach are – licensing history and comparable patents. Interestingly and importantly, these two determinants are also taken into consideration by several antitrust jurisdictions in the world while dealing with the issue of reasonable royalty. III. WHETHER TO REGULATE EXCESSIVE PRICING AND THE MONDERN REASONABLE ROYALTY APPROACH IN THE U.S. A. Whether to regulate excessive pricing? Supply and demand are two key factors that determine a price in a free market. Profits are usually what encourage innovation and attract firms doing businesses in the first place. There is no doubt that a firm sets a price it believes to maximize its profits – which is profit maximization rule in economics. When a monopoly tries to manipulate or disturb the market by setting a lower or higher price that does not go along with profit maximization rule, here are some possible consequences: (1) new entries in the market trying to share the profits; (2) consumers might switch to substitutes of the product in order to pay less; (3) monopoly might lose profits that it would earn otherwise. Simply saying, a free market usually responds to market changes quite well and can function accordingly without too much disruption. Regardless of the free market mechanism, there are still many voices discouraging the prohibition of excessive pricing due to the inherent dangers of regulating prices – such as discouraging investment in research and development activities, impairing innovation, and ultimately harming consumers.[54] Along with the antitrust jurisdictions that prohibit excessive pricing by law, there are studies showing that prohibition of excessive pricing may benefit the market or – the consumers. A 2015 research finds that: “when economies of scale and entry barriers imply a great likelihood of dominant firms not subjecting to regulation but capable of charging supra-competitive prices, excessive pricing regulation is then important for smaller markets.”[55] A study in 2017 further examines the competitive effects of the prohibition of excessive pricing by applying two competitive benchmarks – retrospective benchmark and contemporaneous benchmark to assess the price charged by a dominant firm excessive or not. The study finds that the two benchmarks restrain the dominant firm’s behavior but soften the firm’s behavior when its competing with a rival. By setting certain factors homogeneous, a retrospective benchmark for excessive pricing benefits consumers. While under different circumstances, consumers are worse off and inefficient entries are created. Overall, the study indicates that the competitive effects of prohibition of excessive pricing vary as we consider various factors – such as the nature of competition, the expected fines, incentive to invest in research and development (R&D), cost of litigation and more. [56] As a whole, there are still a great number of concerns about potential dangers of regulating price. However, whether to regulate excessive pricing or not, the fundamental question to ask is still – “how to determine a reasonable price to assess if the price at issue is excessive?” B. The Modern Reasonable Royalty Approach in the U.S. U.S. antitrust agencies do not prohibit excessive pricing. An IPR holder is free to charge a monopoly price just as a monopoly is free to earn its monopoly profits as long as the monopoly price and profits are not resulted from anticompetitive conducts that violate antitrust laws in the U.S. While saying that, U.S. still has a reasonable royalty approach developed under its patent law which is the law Taiwan has copied a lot from. [57] There are different methodologies for the reasonable royalty approach in the U.S., the most common one would be the hypothetical negotiation which was matured from Georgia-Pacific Corp. v. United States Plywood Corpin 1971 (Georgia-Pacific case), ruling that the proper damages in a patent infringement case as – “the amount that a licensor and the infringer would have agreed upon.” By adopting this hypothetical negotiation framework, the case eventually developed a list of 15 determinants as to a reasonable royalty: [58] (1) The royalties received by the patentee for the licensing of the patent in suit, proving or tending to prove an established royalty. (2) The rates paid by the licensee for the use of other patents comparable to the patent in suit. (3) The nature and scope of the license, as exclusive or non-exclusive; or as restricted or non-restricted in terms of territory or with respect to whom the manufactured product may be sold. (4) The licensor's established policy and marketing program to maintain his patent monopoly by not licensing others to use the invention or by granting licenses under special conditions designed to preserve that monopoly. (5) The commercial relationship between the licensor and licensee, such as, whether they are competitors in the same territory in the same line of business; or whether they are inventor and promotor. (6) The effect of selling the patented specialty in promoting sales of other products of the licensee; the existing value of the invention to the licensor as a generator of sales of his non-patented items; and the extent of such derivative or convoyed sales. (7) The duration of the patent and the term of the license. (8) The established profitability of the product made under the patent; its commercial success; and its current popularity. (9) The utility and advantages of the patent property over the old modes or devices, if any, that had been used for working out similar results. (10) The nature of the patented invention; the character of the commercial embodiment of it as owned and produced by the licensor; and the benefits to those who have used the invention. (11) The extent to which the infringer has made use of the invention; and any evidence probative of the value of that use. (12) The portion of the profit or of the selling price that may be customary in the particular business or in comparable businesses to allow for the use of the invention or analogous inventions. (13) The portion of the realizable profit that should be credited to the invention as distinguished from non-patented elements, the manufacturing process, business risks, or significant features or improvements added by the infringer. (14) The opinion testimony of qualified experts. (15) The amount that a licensor (such as the patentee) and a licensee (such as the infringer) would have agreed upon (at the time the infringement began) if both had been reasonably and voluntarily trying to reach an agreement; that is, the amount which a prudent licensee who desired, as a business proposition, to obtain a license to manufacture and sell a particular article embodying the patented invention would have been willing to pay as a royalty and yet be able to make a reasonable profit and which amount would have been acceptable by a prudent patentee who was willing to grant a license. The U.S. reasonable royalty approach and the calculation of reasonable royalty have been evolving since then. The Federal Circuit in a 2011 case held that the long-used and criticized 25 percent rule of thumb is fundamentally flawed for determining a baseline royalty rate in a hypothetical negotiation.[59] The rule suggests that 25% of the expected profits for the product that incorporates the IP at issue as a baseline royalty rate. Practically, the profits earned by the licensee and the revenues of the product are still often taken into consideration nowadays while applying the U.S. reasonable royalty approach. Further, the Ninth Circuit modified some factors in Microsoft Corp. v. Motorola Inc. (2012) which was a case involved with reasonable and non-discriminatory (RAND) commitment, standard essential patents (SEPs), and patent pool. [60] This case raised some important factors to determine a RAND royalty, such as RAND commitment and its purposes, SEPs’ contribution and importance, alternatives of SEPs to the adopted standard, and so on. Comparable patents play a very critical factor in this case in terms of calculating a RAND royalty. Also, it is important to notice that the function of a RAND commitment limits a SEP licensor to royalties that reflect their ex ante values instead of the incremental monopoly power provided by the standard.[61] In Ericsson, Inc. v. D-Link Systems, Inc. (2014), a modified version of the 15 factors was adopted after the Federal Circuit held that – not every factor from the 15 factors in Georgia-Pacific will apply to every case, and courts must instruct the jury on factors that are relevant in the case. Also, the burden of proof is on the implementer (or, the antitrust authority in an excessive pricing case) to establish a baseline royalty with evidence. That royalty then must be assessed to determine if it is excessive. [62]By adopting incremental value approach and incorporating apportionment, the Federal Court here provides a more complete guidance on how to calculate royalties for patents on RAND terms:[63] (1) Importance of RAND commitment; (2) Apportionment of patented features: the royalty for the patented technology must be apportioned from the value of the standard as a whole; (3) Incremental value approach: the royalty must be based on the incremental value of the invention, instead of any value added by the standardization of the invention or the standard itself. Lastly, two factors that were not often discussed while determining a reasonable royalty were applied inPrism Technologies LLC v. Sprint Spectrum L.P. (2017) - previous settlement agreements and cost savings though infringement.[64] In conclusion, the modern reasonable royalty approach under U.S. patent law was evolved from the adopted 15 factors in Georgia Pacific case. The approach then has been developing along with changes of law, development of technology, adoption of SEPs, RAND and FRAND commitments, and more other relevant factors. IV. A PROPOSED ANTITRUST FRAMEWORLK OF REASONABLE ROYALTY FOR TAIWAN Having articulated the past attitude and the current antitrust framework of reasonable royalty in Taiwan, we have pointed out some misunderstandings in the current framework. Having addressed the reasonable royalty approaches under the patent laws in Taiwan and the U.S., we also have found similarities in between – the hypothetical negotiation framework and relevant determinants. Even though there are concerns against prohibition of excessive pricing due to potential dangers of regulating price and supports towards ultimate protection of free competition, TFTC and the courts in Taiwan are still required by law to apply the prohibition of excessive pricing against IPRs for the current time being. Therefore, the most important section and the core of this paper now has come forward – which is a proposed antitrust framework composed of possible methodologies and clearer guidance for Taiwan to deal with the antitrust issue of reasonable royalty in an excessive pricing case. The proposed framework is based on the proposed methodologies in a 2016 paper[65] - which is to apply the hypothetical negotiation framework under U.S. patent law to determine a reasonable royalty or a competitive benchmark in an excessive pricing case. By applying the most relevant factors and adhering to important and correct principles in the case, a reasonable royalty as a baseline is thus determined to evaluate if the price at issue is excessive. Before articulating the proposed framework in a more detailed way, it is important to notice some basic differences between reasonable royalty in a patent infringement case and an excessive pricing case: Table 1 Reasonable Royalty in between a Patent infringement Case and an Excessive Pricing Case Reasonable Royalty in an Excessive Pricing Case Reasonable Royalty in a Patent Infringement Case Base Country Countries that prohibit excessive pricing. U.S. Case Type Antitrust case Patent infringement case Governing Law Antitrust (competition) law Patent law Prohibited Action A prohibited act of charging unfairly high price through abuse of monopoly. A prohibited act of unauthorized making, using, offering, or selling any patented invention. The Reasonable Royalty Issue Through determining a reasonable royalty to evaluate if a firm is charging excessive royalty through abuse of monopoly. Through determining a reasonable royalty to establish damages/compensation for the act of patent infringement. Proof of Harm Having found excessive pricing, competitive harms should be proved to establish an excessive pricing violation. Harm is proved after determining the reasonable royalty. Having proven the act of patent infringement, damages will then be determined based on reasonable royalty. Harm is proved to exist before calculating the damages. Negotiation There was negotiation over royalty before the lawsuit starts. There sometimes had no negotiation over royalty. Reasonable Royalty Approach Apply relevant factors to determine a reasonable royalty, then compare it with the price at issue to decide if the firm is charging excessive price through abuse of monopoly. Apply hypothetical negotiation framework to determine the royalty the licensor and the infringer would have agreed upon if there had been a negotiation instead of an infringement. Relevant Factors There are multiple and various factors applied in different countries, often not systematic or relevant. The 15 factors evolved from Georgia-Pacific, and some modified and new factors developed later on. A. Step 1 – Important Principles to Keep in Mind Regarding the Antitrust Issue of Reasonable Royalty. 1. No presumption of monopoly power: Ownership of IPRs does not necessarily confer monopoly power. 2. IP conducts may possibly constitute antitrust violations: Enforcing IPRs or any seemingly proper IP conduct may still possibly constitute an antitrust violation, so that they shall not be excluded from the application of FTA. 3. No such thing as excessive profit in free market economy: It is the pricing practice conducted by a monopolistic enterprise that should be evaluated in an excessive pricing case, instead of the profits the enterprise earns. 4. Harm to competition is and should be the key to establish an antitrust violation under Article 9 of FTA: Simply charging a perceived excessive price or earning some unjustified profits does not automatically constitute an antitrust violation. It is the competition and consumers that we should protect in terms of any excessive pricing case. Thus, harms to competition and consumers should be proved – such as lower outputs, entry barriers, and negative impacts on innovation or R&D activities. B. Step 2 – Compliance with Article 45 of FTA & IP Guidelines of Taiwan. 1. Firstly, all proper conducts pursuant to all IP laws in Taiwan are excluded to the application of FTA even though there is no clear explanation of what would be proper IP conducts. 2. If Article 45 of FTA does not apply in the case, we should turn to IP Guidelines of Taiwan to see if the involved market conducts or pricing practices would violate the Guidelines. If the Guidelines do not apply here, then we shall turn to Step 3 of the proposed framework. C. Step 3 – If it is a Potential Excessive Pricing Case? Section 2 of Article 9 of FTA articulates - “Monopolistic enterprises shall not engage in improperly setting, maintaining or changing the price for goods or the remuneration for services.[66]” 1. There must be a monopolistic enterprise. 2. The prices of goods or services or the pricing practices involved are reasonably challenged by the implementers or TFTC. [67] D. Step 4 – When would a hypothetical negotiation have taken place? When it is a potential excessive pricing case under Section 2 of Article 9 of FTA, it is time to apply the hypothetical negotiation framework under patent law to determine a reasonable royalty within antitrust framework. While the first thought we come up with is usually “how much the parties would have agreed upon,” what we often ignore is that – “when would a hypothetical negotiation have happened? “The timeframe of the hypothetical negotiation is in fact highly related to what relevant factors we should consider in terms of determining a reasonable royalty. Such timeframe issue thus could cause huge impacts on the amount of damages in a patent infringement case and affect the competitive benchmark in an excessive pricing case. More clarifications are as follows: 1. In a patent infringement case:[68] a. Pure ex ante approach: By assuming the parties would have negotiated over the royalty before the infringement began, such approach reflects an ex ante negotiation in the absence of infringement based on the information available before the infringement. Two supporting reasons are: (1) preservation of incentives; (2) avoidance or lowering the cost of patent holdup.[69] b. Pure ex post approach: This approach sets the negotiation reached on some later date, such as the date of judgement or any time after the infringement. Such approach could possibly provide more available and provable information to determining a royalty but could also give the patentee more bargaining power when the patentee is holding an injunction against the infringer. Figure 1 Timeframes of the Hypothetical Negotiation Applying Pure Ex Ante Approach and Pure Ex Post Approach c. Contingent Ex Ante Approach: Pros and concerns when applying pure ex ante and pure ex post approaches are out there to be noted. While a proposed approach claims to address the issues of patent holdup and bargaining power at the same time – which is called contingent ex ante approach. This approach sets the negotiation prior infringement reached contingent on the ex post information, arguing that ex post information provides a better measure for the true value of the patented technology. Further, it is said to be able to take new and changed circumstances into account in every individual infringement case. Here is a simple example presented in the paper:[70] (1) A $500,000 royalty might be agreed upon based on the parties’ expectation that the infringer would earn $1 million above what it would earn if it used the next-best available non-infringing patent. (2) At the date of judgement, the infringer is proven to earn $1.5 million instead of $1 million. This $1.5 million earning would be the ex post information applied in an ex ante negotiation. On the other hand, if the proven earning is only $500,000, then the royalty the parties might have agreed upon would be lower. (3) By applying contingent ex ante approach, it is argued that the patent hold-up would be avoided and the bargaining power between the parties would be balanced. Figure 2 Timeframes of the Hypothetical Negotiation Applying Contingent Ex Ante Approach 2. In an excessive pricing case: Applying the hypothetical negotiation framework under patent law in an excessive pricing case is much more difficult on one matter – the timeframe discussed above. Some important reasons are as follow: (1) Excessive pricing cases involve comparing a competitive benchmark with the price at issue, yet the prices in a case could be changing over time. (2) There were already negotiations over royalty before an excessive pricing lawsuit starts. (3) Involvement of FRAND and SEPs only make it more complicated to determine a reasonable royalty while facing the timeframe issue. E.g. the timing of a patent’s incorporation into a standard is critical and affects the value of the invention. Figure 3 Excessive Pricing Case and the Timeframe Issue E. Step 5 – If there are FRAND or RAND terms? Royalties negotiated on FRAND or RAND terms (FRAND royalties) can be and are usually different from those without. FRAND royalties may involve the following factors which often consequently affect royalties in real world: 1. FRAND obligations and terms: such as fairness, royalty free, grant back provision, exclusivity and other reciprocal terms. 2. Timing of the establishment of a standard: A patent may exist before the establishment of an industrial standard. As this patent is considered essential to a standard and also is included in such standard, the value of such patent – SEP usually goes up.[71] 3. Cooperation between SEP holders: the number of SEP holders and the number of SEPs included in a standard can be influential. 4. Other factors: standard setting organizations’ policies, threat of injunction, patent hold-up and hold-out, royalty stacking, other available and comparable technologies, and relationship between licensors and licensees. F. Step 6 – Consider the Most Relevant Factors. No matter what approach or timeframe of hypothetical negotiation gets adopted in an excessive pricing case, the most relevant factors to consider in determining a reasonable royalty are as follow: 1. Comparable patents The best potential non-infringing alternatives should be the top determinant. What we usually consider as alternatives here are the existing patents in the marketplace since it would be impractical to include expired or invalid patents as comparable patents. But if we take the issue of the timeframe of a hypothetical negotiation into consideration, the status of the patents could be different – which means the hypothetical negotiation could have happened when there were more or less comparable patents. Undoubtedly, comparability is hard to judge. Loads of factors have been taken into account – technical and economic standpoints, the underlying technology, timing of the licensing, previous settlements or litigations, and other more. As noted here, comparable patents are provided as evidence to determining a reasonable royalty – not to its admissibility. Further, here are more difficulties while looking for comparable patents: a. Lots of technology-related royalties nowadays are negotiated on a patent portfolio basis using the end-user device as the royalty base. Both end-user based and portfolio based calculations make it harder to extract the value of an individual patent. b. Cross-licensing or business relationships are sometimes built in exchange of patent licensing. It means that there sometimes has no cash payment involved to know the values of patents. c. Should the allegedly comparable patents cover foreign patents? 2. FRAND royalties: a. FRAND or RAND commitment and its importance. b. Number of SEPs and number of SEP holders in a standard setting. c. Proper apportionment: By the reason that not all patents are created equal or of the same value, the value of an individual patent’s contribution to the standard and the end product is a critical factor when determining a FRAND royalty. As noted here for clarification, even though the Federal Circuit in the famous Ericsson v. D-Link case stated that a FRAND royalty should not include the value that a technology gains from simply being included in a standard, it should not be interpreted as a complete exclusion of any of a standard’s value. When a patented technology in fact creates values for a standard due to its inclusion, these values should definitely be considered as contribution and an important factor.[72] G. Step 7 – Consider Other Factors 1. Other factors may possibly be considered a. The terms and scope of the licensing agreement, as exclusive, non-exclusive, restrictive, or non-restrictive. b. The nature and benefits of the technology or invention. c. Licensor’s monopoly power, and its policies or programs to maintain or preserve such power. d. Licensing history between the parties, and between the licensor and other firms. e. Investments made to implement the technology or the standard. f. Barriers to entry, it could be legal barriers, exclusive agreements, economies of scale, or network effect.[73] As for antitrust of excessive pricing in Taiwan, a paper suggests that entry barriers should be one of the keys to determine if TFTC should step in. That is to say - when there are entry barriers delaying or barring new entries in a market, TFTC should possibly have jurisdiction and a case according to the types of the barriers. g. Royalty stacking and patent hold-up and hold-out. h. Smallest saleable component rule: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) amended its patent policy in 2015 and included the smallest saleable Compliant Implementationas an important consideration in terms of determining a reasonable royalty.[74] 2. Factors not recommended to be considered. a. Profits earned from charging the allegedly excessive royalty. b. The profitability, commercial success, popularity, advantages, utilities, and the sales of the patented products. c. The value of the pure adoption of the standard. d. Commercial and business relationships involved. e. Other non-competition, non-patent-related, or pure business factors. H. Step 8– Compare the Reasonable Royalty to the Alleged Excessive Price 1. The determined reasonable royalty is a baseline or what we call a competitive benchmark. It should not be a minimal royalty a patent owner can charge. 2. As for practicality, it is allowed to be more than just reasonable royalty to be compensated to the patent owner in a patent infringement case. Just like a firm can charge a price more than the cost of its product. Therefore, the price at issue should not be necessarily excessive when the determined reasonable royalty is greater than the alleged excessive price. V. CONCLUSION Excessive pricing cases involving the antitrust issue of reasonable royalty can be a matter of tremendous cost of litigation, fines of billion dollars, and unimaginable potential harms to competition. The great dangers involved through regulating price can lead to negative impacts on innovation, industries, and consumers - consequently to the ultimate failure of protection of competition. Putting aside the doubts about the prohibition of excessive pricing, I respectfully propose an antitrust framework of reasonable royalty in this paper with a sincere goal to help Taiwan with the issue of reasonable royalty in any excessive pricing case in the future. Lastly, I sincerely address the most essential and ultimate principle of antitrust here, again - it is and should always be the competition that antitrust laws and agencies aim to protect, not competitors, prices or only the consumers.[75] [1] Anti-Monopoly Law of the People’s Republic of China, Law Info China, http://www.lawinfochina.com/display.aspx?lib=law&id=0&CGid=96789 (last visited Aug. 6, 2019); The Antimonopoly Act, Japan Fair Trade Commission, http://www.jftc.go.jp/en/legislation_gls/amended_ama09/amended_ama15_01.html(last visited Mar.9, 2018); Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act, Fair Trade Commission of Korea, http://www.moleg.go.kr/english/korLawEng?pstSeq=54772(last visited Aug. 6, 2019); Fair Trade Act, Fair Trade Commission of Taiwan, https://www.ftc.gov.tw/law/EngLawContent.aspx?lan=E&id=29 (last visited Mar.9, 2018). [2] Anti-monopoly Law of the People's Republic of China §17(1), available at http://www.china.org.cn/government/laws/2009-02/10/content_17254169.htm (last visited Mar.12, 2018). [3]Huawei Technologies Co. v. InterDigital Technology Co., Guangdong High Court Decision No.306 (2013), available at http://www.mlex.com/China/Attachments/2014-04-17_BT5BM49Q967HTZ82/GD%20verdict.pdf (last visited Mar.9, 2018);CLEARY GOTTLIEB STEEN & HAMILTON LLP, China’s NDRC Concludes Qualcomm Investigation, Imposes Changes in Licensing Practices (Mar. 16, 2015), https://www.clearygottlieb.com/-/media/organize-archive/cgsh/files/publication-pdfs/chinas-ndrc-concludes-qualcomm-investigation-imposes-changes-in-licensing-practices.pdf (last visited Mar.9, 2018). [4] THE MINISTRY OF COMMERCE OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA, Full text of the Draft of the Anti-Monopoly Guidelines on the Abuse of Intellectual Property Rights (2017), http://fldj.mofcom.gov.cn/article/zcfb/201703/20170302539418.shtml (last visited Mar. 12, 2018). [5]Bruce Kobayashi, Douglas Ginsburg, Joshua Wright & Koren Wong-Ervin,Comment of the Global Antitrust Institute, Antonin Scalia Law School, George Mason University, on the Anti-Monopoly Commission of the State Council's Anti-Monopoly Guidelines against Abuse of Intellectual Property Rights, GEORGE MASON LAW & ECONOMICS RESEARCH PAPER, No.17-19, available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2952414 (last visited Mar.12, 2018). [6] European Commission is the competition authority within European Union. [7] TheTreaty on the Functioning of the European Union §102(a), available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2016:202:FULL&from=EN (last visited Mar.12, 2018). [8] United Brands Company and United Brands Continentaal BV v Commission of the European Communities, Case 27/76 (1978). [9] Antitrust: Commission sends Statement of Objections to Motorola Mobility on potential misuse of mobile phone standard-essential patents- Questions and Answers, European Commission, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-13-403_en.htm (last visited Mar.12, 2018); see also Protecting consumers from exploitation-Chillin’ Competition Conference, Brussels, 21 November 2016, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2014-2019/vestager/announcements/protecting-consumers-exploitation_en (last visited Mar.12, 2018). [10] Autortiesību un komunicēšanās konsultāciju aģentūra / Latvijas Autoru apvienība v. Konkurences padome, C-177/16(2017). [11] TheTreaty on the Functioning of the European Union §267(a), available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:12008E267:en:HTML (last visited Mar.13, 2018). [12] Miranda Cole,Kevin Coates&Siobhan L.M. Kahmann, Welcome clarifications by the EU Court on the concept of excessive pricing, Covington & Burling LLP - Inside Tech Media (Sep. 15, 2017), https://www.insidetechmedia.com/2017/09/15/welcome-clarifications-by-the-eu-court-on-the-concept-of-excessive-pricing/ (last visited Mar.13, 2018). [13] Martin André Dittmer & Sofie Kyllesbech Andersen, Recent decisions on excessive pricing, abuse of dominance, cartel penalties and gun jumping (2018), https://www.internationallawoffice.com/Newsletters/Competition-Antitrust/Denmark/Gorrissen-Federspiel/Recent-decisions-on-excessive-pricing-abuse-of-dominance-cartel-penalties-and-gun-jumping (last visited Jan. 17, 2019). [14] Michal S. Gal, Monopoly Pricing as an Antitrust Offense in the U.S. And the EC: Two Systems of Belief About Monopoly? ANTITRUST BULLETIN, 49, 343-384 (2004), available athttps://ssrn.com/abstract=700863 (last visited Mar.14, 2018). [15] U.S. Federal Trade Commission v. Qualcomm Incorporated ( N.D. Cal. Filed Jan. 17, 2017), available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/170117qualcomm_redacted_complaint.pdf (last visited Mar. 14, 2018). [16] Federal Trade Commission v. Qualcomm Incorporated, Case No. 5:17-cv-00220-LHK (D. Northern District of California, filed Feb.1, 2017). [17] FAIR TRADE COMMISSION, Dissenting Statement of Commissioner Maureen K. Ohlhausen In the Matter of Qualcomm, Inc. (Jan. 17,2017), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/170117qualcomm_mko_dissenting_statement_17-1-17a.pdf (last visited Mar. 2, 2018). [18] Taiwan Fair Trade Act §9(1) (2017), available at: http://law.moj.gov.tw/Eng/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?PCode=J0150002 (last visited Mar. 2, 2018). [19] Bruce H. Kobayashi, Douglas H. Ginsburg, Joshua D. Wright, and Koren W. Wong-Ervin, “Excessive Royalty” Prohibitions and the Dangers of Punishing Vigorous Competition and Harming Incentives to Innovate, CPI ANTITRUST CHRONOCLE, 4(3) (2016). [20] Kung-Chung Liu, Interface between IP and Competition Law in Taiwan, THE JOURNAL OF WORLD INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY, 8(6), 735–760 (2005). [21] Pei-Fen Hsieh, Antitrust Regulatory Measures Under the trend towards Bureaucratic Regulation- A Study on Consent Decree, FAIR TRADE QUARTERLY, 13(1), 166 (2005). [22] Taiwan Fair Trade Commission, Meeting Minutes No.352 (1998). [23] Hong Xuan, On principles in tackling technology license and market competition, 112-113 (2008). [24] TAIWAN FAIR TRADE COMMISION, Meeting Minutes No.480 of Taiwan Fair Trade Commission (2001), https://www.ftc.gov.tw/upload/upload-90R480_REC.txt (last visited Feb. 7, 2018). [25] Kung-Chung Liu & Vick Chien, Analysis of and Comments on CD-R-related Cases: Focusing on Competition Law and Patent Compulsory Licensing Issues, FAIR TRADE QUARTERLY, 17(1), 2 (2005). [26] Sony and Taiyo Yuden did not appeal against the administrative decisions in 2010; therefore their cases were affirmed before 2015. See TAIWAN FAIR TRADE COMMISSION, Administrative Decision No.104027 (2015), https://www.ftc.gov.tw/uploadDecision/269b6dff-a0fc-46a0-8512-ca5f716732bb.pdf (last visited Feb. 7, 2018). [27] Taipei High Administrative Court, Philips Electronics NV v. TFTC, Decision No. 00908 (2003). [28] TAIWAN FAIR TRADE COMMISSION, Administrative Decision No. 095045 (2006), https://www.ftc.gov.tw/uploadDecision/2005302-0950426_002_095d045.pdf (last visited Feb. 23, 2018). [29] Taiwan Intellectual Property Court Appeal Case No.14 (2008), https://law.judicial.gov.tw/FJUD/data.aspx?ro=10&q=cd8bdbb8d80f8d587805c863b2e64c55&gy=jcourt&gc=IPC&sort=DS&ot=in (last visited Aug. 6, 2019). [30] TAIWAN FAIR TRADE COMMISSION, Administrative Decision No. 098156 (2009) http://www.ftc.gov.tw/uploadDecision/faed94a8-34ce-4f8e-b59a-239a9eaece1d.pdf (last visited Feb. 23, 2018). [31] Supreme Court of Taiwan, Case No.883 (2012), https://law.judicial.gov.tw/FJUD/data.aspx?ro=0&q=033765ef814495b27d346fcbd9f38606&gy=jcourt&gc=TPS&sort=DS&ot=in (last visited Aug. 6, 2019). [32] TAIWAN FAIR TRADE COMMISSION, Administrative Decision No. 104027 (2015) https://www.ftc.gov.tw/uploadDecision/269b6dff-a0fc-46a0-8512-ca5f716732bb.pdf (last visited Feb. 26, 2018). [33] TAIWAN FAIR TRADE COMMISSION, Administrative Decision No.106094 (2017) https://www.ftc.gov.tw/uploadDecision/561633e4-42bd-4a4f-a679-c5ae5226966b.pdf (last visited Mar. 2, 2018). [34] Fair Trade Act of 2017 §9(1), available at: http://law.moj.gov.tw/Eng/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?PCode=J0150002 (last visited Mar. 2, 2018). [35] id, at Page 61-62. [36] Settlement between TFTC and Qualcomm, TAIWAN FTC NEWSLETTER, August 10, 2018, https://www.ftc.gov.tw/internet/main/doc/docDetail.aspx?uid=126&docid=15551 (last visited Nov. 30, 2018). [37] TAIWAN FAIR TRADE COMMISSION, Record of Commission Meeting No. 1396 (Nov. 2018), https://www.ftc.gov.tw/upload/b0aa3b61-d0e7-41c4-b6a0-b1e6a472ee04.pdf (last visited Nov. 30, 2018). [38] TAIWAN FAIR TRADE COMMISSION, Qualcomm’s Investment Plan under the Settlement, (Oct. 2018), https://www.ftc.gov.tw/upload/ee937bcf-68b9-4751-b2da-b636c46b0faa.pdf (last visited Nov. 30, 2018). [39] The latest amendment of the Fair Trade Act of Taiwan was proposed in the October of 2018, waiting to be reviewed. https://join.gov.tw/policies/detail/898e30a4-1ee8-491b-8c5a-5fbdbb5973f9 (last visited Jan. 18, 2019). [40] See Fair Trade Act of 2017 §45:”No provision of this Act shall apply to any proper conduct in connection with the exercise of rights pursuant to the provisions of the Copyright Act, Trademark Act, Patent Act or other Intellectual property laws.”; available at http://law.moj.gov.tw/Eng/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?PCode=J0150002 (last visited Mar. 5, 2018); also see FAIR TRADE COMMISSION, Administrative Statement No. 02678 (2000), https://www.ftc.gov.tw/internet/main/doc/docDetail.aspx?uid=225&docid=431 (last visited Mar.25, 2018). [41] Legislative Rationales of Fair Trade Act of 1991, available at https://www.ftc.gov.tw/law/LawContent.aspx?id=FL011898 (last visited Aug. 6, 2019). [42] Guidelines on Technology Licensing, Fair Trade Commission, https://www.ftc.gov.tw/internet/main/doc/docDetail.aspx?uid=163&docid=227 (last visited Aug. 6, 2019). [43] id, §3. [44] id, §5(C): “Stipulations that, for ease of calculation, fees for licensed technology that is part of a manufacturing process or that subsists in component parts are to be calculated on the basis of the quantity of finished goods manufactured or sold that employ the licensed technology, or the quantity of raw materials or component parts used that employ the licensed technology, or the number of times such materials or parts are used in the manufacturing process.”; see also §6(L): “Requirements that the licensee pay licensing fees based on the quantity of a particular type of good manufactured or sold irrespective of whether the licensee used the licensed technology.” [45] id, §5: “The following kinds of technology licensing arrangement stipulations do not intrinsically violate the provisions of the Act on restraint of competition or unfair competition, with the exception of those improper matters to be found after reviewed in accordance with Point 5(C) and 5(D)…” [46] Fair Trade Act §9(2): “Monopolistic enterprises shall not engage in any one of the following conducts… improperly set, maintain or change the price for goods or the remuneration for services,” available at http://law.moj.gov.tw/Eng/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?PCode=J0150002 (last visited Mar. 8, 2018). [47] Douglas H. Ginsburg & Joshua D. Wright, Whither Symmetry? Antitrust Analysis of Intellectual Property Rights at the FTC and DOJ, COMPETITIN POLICY INTERNATION, 9 (2) (2013). [48] Id. [49] id, Section 1-3 of § 97(1). [50] id, Section 3 of §97(1) :”the amount calculated on the basis of reasonable royalties that may be collected from exploiting the invention patent being licensed.”; see also The 2013 Amendment to Patent Act of Taiwan, List of Amendments to Patent Act of Taiwan, http://www.6law.idv.tw/6law/law2/專利法歷年修正條文及理由.htm#_%EF%BC%8E12%EF%BC%8E%E4%B8%80%E7%99%BE%E9%9B%B6%E4%BA%8C%E5%B9%B4%E4%BA%94%E6%9C%88%E4%B8%89%E5%8D%81%E4%B8%80%E6%97%A5%EF%BC%88%E5%85%A8%E6%96%87%E4%BF%AE%E6%AD%A3%EF%BC%89 (last visited Mar. 8, 2018). [51] id. [52] Intellectual Property Court of Taiwan Case No.38 (2014); see also Intellectual Property Court of Taiwan Case No.24 (2017); Chung-Lun Shen, Taiwan Supreme Court to Clarify Distinction between Patent Damages and Unjust Enrichment: Koninklijke Philips N. V. v. Gigastorage Corporation, IP OBSERVER, 18 (2017). [53] <與飛利浦專利訴訟 國碩扳回一城>,經濟日報UDN,https://money.udn.com/money/story/5607/3393179 (last visited Jan. 19, 2019). [54] Bruce H. Kobayashi, Douglas H. Ginsburg, Joshua D. Wright, and Koren W. Wong-Ervin, “Excessive Royalty” Prohibitions and the Dangers of Punishing Vigorous Competition and Harming Incentives to Innovate, CPI ANTITRUST CHRONOCLE, 4(3) (2016). [55] Reena Das Nair & Pamela Mondliwa, Excessive Pricing revisited: what is a competitive price?, Presented at Conference: 1st ANNUAL COMPETITION AND ECONOMIC REGULATION (ACER) WEEK, SOUTHERN AFRICA (2015), https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Reena_Das_Nair/publication/290440699_Excessive_Pricing_revisited_what_is_a_competitive_price/links/5698d5f408ae34f3cf2070dd/Excessive-Pricing-revisited-what-is-a-competitive-price.pdf (last visited June. 5, 2018). [56] David Gilo & Yossi Spiegely, The Antitrust Prohibition of Excessive Pricing, INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATION, Elsevier, vol. 61(C)(2018). [57] 35 U.S. Code § 284. [58] Georgia-Pacific Corp v. United States Plywood Corp, 318 F. Supp. 1116 (NY.S.D.N.Y. 1970). [59] Uniloc USA, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 632 F. 3d 1292 (Fed. Cir., 2011). [60] Microsoft Corp. v. Motorola Inc,696 F.3d 872 (9th Cir. 2012). [61] William H. Page,Judging Monopolistic Pricing: F/RAND and Antitrust Injury, TEXAS INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL, 22, 181-208 (2014), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/588 (last visited Mar. 28, 2018). [62] Ericsson, Inc. v. D-Link Systems, 773 F.3d 1201 (Fed.Cir. 2014). [63] Anne Layne-Farrar & Koren W. Wong-Ervin, An Analysis of the Federal Circuit's Decision in Ericsson v. D-Link,Competition Policy International, CPI Antitrust Chronicle, (1) (2015), available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2669269 (last visited Mar. 29, 2018), see also Huntern Shu, Determination of royalties in Ericsson v. D-Link, Science & Technology Policy Research and Information Center (STPI) (2015), http://iknow.stpi.narl.org.tw/post/Read.aspx?PostID=10945 (last visited Mar. 29, 2018). [64] Prism Technologies LLC v. Sprint Spectrum L.P., No.16-1456 (Fed. Cir. 2017). [65] GINSBURG, KOBAYASHI, WONG-ERVIN & WRIGHT ET AL., supra note 19. [66] Id. [67] Fair Trade Act §7. [68] Norman V. Siebrasse &Thomas F. Cotter, A New Framework for Determining Reasonable Royalties in Patent Litigation, FLORIDA LAW REVIEW, 68 (2016), available at : http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol68/iss4/1 (last visited Mar. 29, 2018). [69] U.S. FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION, The Evolving IP Marketplace: Aligning Patent Notice and Remedies With Competition (2011), https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/evolving-ip-marketplace-aligning-patent-notice-and-remedies-competition-report-federal-trade/110307patentreport.pdf (last visited Jan. 23, 2019). [70] id. at 21. [71] Standard-essential patents, COMPLETION POLICY BRIEF, 5 (2014). [72] id. at Page17. [73] Ma, Tay-cheng,Regulation of the Exploitative Abuse: Policy Initiative and Practical Dilemma, Fair Trade Quarterly 17(1) (2009). [74] INSTITUTE OF ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRINICS ENGINEERS, IEEE-SA STANDARDS BOARD BYLAWS (2015),https://standards.ieee.org/about/policies/bylaws/sect6-7.html (last visited Jan. 22, 2019). [75] Douglas H. Ginsburg & Joshua D. Wright, The Goals of Antitrust: Welfare Trumps Choice, FordhamLAW REVIEW, 81 (2013), available at https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol81/iss5/9 (last visited Mar. 11, 2018).

The Dispute on WTO TRIPS IP Waiver Proposal and the Impact on TaiwanThe Dispute on WTO TRIPS IP Waiver Proposal and the Impact on Taiwan 1. IP Waiver proposal On October 2, 2020, South Africa and India summit a joint proposal (IP/C/W/669) (hereinafter as “first proposal”) for TRIPS council of the World Trade Organization(WTO), titled “Waiver from Certain Provisions of the Trips Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of Covid-19”, called for temporary IP waiver of intellectual property in response for Covid-19 pandemic. In first proposal, it supported a waiver from the implementation or application of Sections 1, 4, 5, and 7 of Part II of the TRIPS Agreement in relation to prevention, containment or treatment of COVID-19, which directs to copyright and related rights, industrial designs, patents and protection of undisclosed information. All enforcement measures under part III of the TRIPS agreement such as civil and administrative procedures and remedies, border measures and criminal procedures for protecting aforesaid intellectual property shall also be waived until widespread vaccination is in place globally, and the majority of the world's population has developed immunity[1]. On May 25, 2021, the first proposal was revised (IP/C/W/669/Rev.1, hereinafter as “second proposal”) and resubmitted for WTO by the African Group, The Plurinational State Of Bolivia, Egypt, Eswatini, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Kenya, The Ldc Group, Maldives, Mozambique, Mongolia, Namibia, Pakistan, South Africa, Vanuatu, The Bolivarian Republic Of Venezuela and Zimbabwe[2]. In the second proposal, the scope of IP waiver was revised to be limited to "health products and technologies" used for the prevention, treatment or containment of COVID-19, and the minimum period for IP waiver was 3 years from the date of decision. 2. The Pros and Cons of IP Waiver proposal The IP waiver proposal is currently supported by over 100 WTO members. However, in order to grant the waiver, the unanimous agreement of the WTO's 159 members would be needed[3], but if no consensus is reached, the waiver might be adopted by the support of three-fourths of the WTO members[4]. The reason for IP waiver mainly focus on the increase of production and accessibility of the vaccines and treatments, since allowing multiple actors to start production sooner would enlarge the manufacturing capacity than concentrate the manufacturing facilities in the hands of a small number of patent holders[5]. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) also support IP waiver proposal to prevent the chilling effect of patents as hindrances of the introduction of affordable vaccines and treatment in developing countries[6], and urges wealthy countries not to block IP waiver to save lives of billions of people[7]. Most opponents against IP waiver proposal are rich countries such as European Union (EU), UK, Japan, Switzerland, Brazil, Norway, Canada, Australia[8]. On May 5, 2021, United States Trade Representative (USTR) announced its support the IP waiver, but only limited into vaccine[9]. EU was the main opponent against IP waiver proposal at the WTO[10]. On June 4, 2021, EU offered an alternative plan to replace IP waiver proposal. Specifically, EU proposed that WTO members should take multilateral trade actions to expand the production of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments, and ensure universal and fair access thereof. EU calls for WTO members to ensure that COVID-19 vaccines, treatments and their components can cross borders freely, and encourage producers to expand their production and provide vaccines with an affordable price. As to IP issues, EU encourages to facilitate the exploitation of existing compulsory licensing systems on TRIPS, especially for vaccine producers without the consent of the patent holder[11]. Many pharmaceutical companies also express dissent opinions against the IP waiver proposal. The International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA) indicated that the proposal would let unexperienced manufacturers, which are devoid of essential know-how, join into vaccine supply chains and crowd out the established contractors[12]. The chief patent attorney for Johnson & Johnson pointed out that since the existing of IP rights not only promote the development of safe and effective vaccines at record-breaking speed, but also allow the IP owner to enter into agreements with appropriate partners to ensure the production and distribution of qualitied vaccines, the problem resides in infrastructure rather than IP. Thus, instead of IP waiver, boosting adequate health care infrastructure, vaccine education and medical personnel might be more essential for COVID-19 vaccines equitably and rapidly distributed[13]. Pfizer CEO warned that since the production of Pfizer’s vaccine would require 280 different materials and components that are sourced from 19 countries around the world, the loss of patent protection may trigger global competition for these vaccine raw materials, and thus threaten vaccine production efficiency and affect vaccine safety[14]. Moderna CEO said that he would not worry about the IP waiver proposal since Moderna had invested heavily in its mRNA supply chain, which did not exist before the pandemic, manufacturers who want to produce similar mRNA vaccines will need to conduct clinical trials, apply for authorization, and expand the scale of production, which may take up to 12 to 18 months[15]. 3. Conclusion The grant of the IP waiver proposal might need the consensus of all WTO members. However, since the proposal might not be supported by several wealth countries, which might reflect the interest of big pharmaceutical companies, reach the unanimously agreement between all WTO members might be difficult. Besides, the main purpose for IP waiver is to increase the production of vaccines and treatments. However, when patent protection was lifted, a large number of new pharmaceutical companies lacking necessary knowhow and experience would join the production, which might not only result in snapping up the already tight raw materials, but also producing uneven quality of vaccines and drugs. Since patent right is only one of the many conditions required for the production of vaccines and drugs, IP waiver might not help increase the production immediately. Thus, other possible plans, such as the alternative plan proposed by EU, might also be considered to reduce disputes and achieving the goal of increasing production. As to the impact of the IP waiver proposal for Taiwan, it can be analyzed from two aspects: 1. Whether Taiwan need IP waiver to produce COVID-19 vaccine and drugs in need Since there is an established patent compulsory licensing system in Taiwan, the manufacture and use of COVID-19 vaccine and drugs might be legally permissible. To be specific, Article 87 of Taiwan Patent Act stipulates: “In response to national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency, the Specific Patent Agency shall, in accordance with an emergency order or upon notice from the central government authorities in charge of the business, grant compulsory licensing of a patent needed, and notify the patentee as soon as reasonably practicable.” Thus, in response to national emergency such as COVID-19 pandemic, Taiwan Intellectual Property Office (TIPO) could grant compulsory licensing of patents needed for prevention, containment or treatment of COVID-19, in accordance with emergency order or upon notice from the central government authorities. In fact, in 2005, in response to the avian flu outbreaks, TIPO had grant a compulsory licensing for Taiwan patent No.129988, the Tamiflu patent owned by Roche. 2. Whether IP Waiver would affect Taiwan’s pharmaceutical or medical device industry In fact, there are many COVID-19 related IP open resources for innovators to exploit, such as Open COVID Pledge[16], which provides free of charge IPs for use. Even for vaccines, Modena had promised not to enforce their COVID-19 related patents against those making vaccines during COVID-19 pandemic[17]. Therefore, currently innovators in Taiwan could still obtain COVID-19 related IPs freely without overall IP Waiver. Needless to say, since many companies in Taiwan still work for the research and development of COVID-19-related medical device and drugs, sufficient IP protection could guarantee their profit and stimulate future innovation. Accordingly, since Taiwan could produce COVID-19 vaccines and drugs in need domestically by existing patent compulsory licensing system, and could obtain other COVID-19 related IPs via global open IP resources, in the meantime IP protection would secure Taiwan innovator’s profit, IP waiver proposal might not result in huge impact on Taiwan. [1]Waiver From Certain Provisions Of The Trips Agreement For The Prevention, Containment And Treatment Of Covid-19, WTO, Oct 2, 2020, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/IP/C/W669.pdf&Open=True (last visited July 5, 2021) [2]Waiver From Certain Provisions Of The Trips Agreement For The Prevention, Containment And Treatment Of Covid-19 Revised Decision Text, WTO, May 25, 2021, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/IP/C/W669R1.pdf&Open=True (last visited July 5, 2021) [3]COVID-19 IP Waiver Supporters Splinter On What To Cover, Law360, June 30, 2021, https://www.law360.com/articles/1399245/covid-19-ip-waiver-supporters-splinter-on-what-to-cover- (last visited July 5, 2021) [4]The Legal Framework for Waiving World Trade Organization (WTO) Obligations, Congressional Research Service, May 17, 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10599 (last visited July 5, 2021) [5]South Africa and India push for COVID-19 patents ban, The Lancet, December 5, 2020, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32581-2/fulltext (last visited July 5, 2021) [6]MSF supports India and South Africa ask to waive COVID-19 patent rights, MSF, Oct 7, 2020, https://www.msf.org/msf-supports-india-and-south-africa-ask-waive-coronavirus-drug-patent-rights (last visited July 5, 2021) [7]MSF urges wealthy countries not to block COVID-19 patent waiver, MSF, Feb. 3, https://www.msf.org/msf-urges-wealthy-countries-not-block-covid-19-patent-waiver (last visited July 5, 2021) [8]Rich countries are refusing to waive the rights on Covid vaccines as global cases hit record levels, CNBC, Apr. 22, 2021,https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/22/covid-rich-countries-are-refusing-to-waive-ip-rights-on-vaccines.html (last visited July 5, 2021) [9]Statement from Ambassador Katherine Tai on the Covid-19 Trips Waiver, May 5, 2021, https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2021/may/statement-ambassador-katherine-tai-covid-19-trips-waiver (last visited July 5, 2021) [10]TRIPS waiver: EU Council and European Commission must support equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for all, Education International, June 9, 2021, https://www.ei-ie.org/en/item/24916:trips-waiver-eu-council-and-european-commission-must-support-equitable-access-to-covid-19-vaccines-for-all (last visited July 5, 2021) [11]EU proposes a strong multilateral trade response to the COVID-19 pandemic, European Commission, June 21, 2021, https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=2272 (last visited July 5, 2021) [12]Drugmakers say Biden misguided over vaccine patent waiver, Reuters, May 6, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/pharmaceutical-association-says-biden-move-covid-19-vaccine-patent-wrong-answer-2021-05-05/ (last visited July 5, 2021) [13]J&J's Chief Patent Atty Says COVID IP Waiver Won't Work, Law360, Apr. 22, 2021, https://www.law360.com/ip/articles/1375715?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=section (last visited July 5, 2021) [14]Pfizer CEO opposes U.S. call to waive Covid vaccine patents, cites manufacturing and safety issues, CNBC, May 7, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/07/pfizer-ceo-biden-backed-covid-vaccine-patent-waiver-will-cause-problems.html (last visited July 5, 2021) [15]Moderna CEO says he's not losing any sleep over Biden's support for COVID-19 vaccine waiver, Fierce Pharma, May 6, 2021, https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/moderna-ceo-says-he-s-not-losing-any-sleep-over-biden-s-endorsement-for-covid-19-ip-waiver (last visited July 5, 2021) [16]Open Covid Pledge. https://opencovidpledge.org/ (last visited July 7, 2021) [17]Statement by Moderna on Intellectual Property Matters during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Moderna, Oct. 8, 2020, https://investors.modernatx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/statement-moderna-intellectual-property-matters-during-covid-19 (last visited July 7, 2021)