Finland’s Technology Innovation System

I. Introduction

When, Finland, this country comes to our minds, it is quite easy for us to associate with the prestigious cell-phone company “NOKIA”, and its unbeatable high technology communication industry. However, following the change of entire cell-phone industry, the rise of smart phone not only has an influence upon people’s communication and interaction, but also makes Finland, once monopolized the whole cell-phone industry, feel the threat and challenge coming from other new competitors in the smart phone industry. However, even though Finland’s cell-phone industry has encountered frustrations in recent years in global markets, the Finland government still poured many funds into the area of technology and innovation, and brought up the birth of “Angry Birds”, one of the most popular smart phone games in the world. The Finland government still keeps the tradition to encourage R&D, and wishes Finland’s industries could re-gain new energy and power on technology innovation, and indirectly reach another new competitive level.

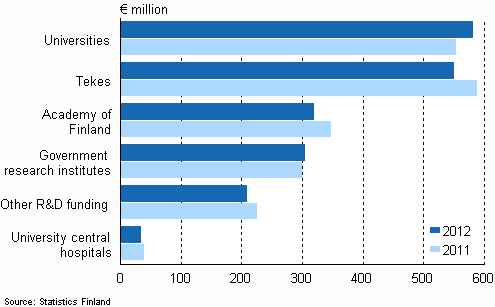

According to the Statistics Finland, 46% Finland’s enterprises took innovative actions upon product manufacturing and the process of R&D during 2008-2010; also, the promotion of those actions not merely existed in enterprises, but directly continued to the aspect of marketing and manufacturing. No matter on product manufacturing, the process of R&D, the pattern of organization or product marketing, we can observe that enterprises or organizations make contributions upon innovative activities in different levels or procedures. In the assignment of Finland’s R&D budgets in 2012, which amounted to 200 million Euros, universities were assigned by 58 million Euros and occupied 29% R&D budgets. The Finland Tekes was assigned by 55 million Euros, and roughly occupied 27.5% R&D budgets. The Academy of Finland (AOF) was assigned by 32 million Euros, and occupied 16% R&D budges. The government’s sectors were assigned by 3 million Euros, and occupied 15.2% R&D budgets. Other technology R&D expenses were 2.1 million Euros, and roughly occupied 10.5% R&D. The affiliated teaching hospitals in universities were assigned by 0.36 million Euros, and occupied 1.8% R&D budgets. In this way, observing the information above, concerning the promotion of technology, the Finland government not only puts more focus upon R&D innovation, but also pays much attention on education quality of universities, and subsidizes various R&D activities. As to the Finland government’s assignment of budges, it can be referred to the chart below.

As a result of the fact that Finland promotes industries’ innovative activities, it not only made Finland win the first position in “Growth Competitiveness Index” published by the World Economic Forum (WEF) during 2000-2006, but also located the fourth position in 142 national economy in “The Global Competitiveness Report” published by WEF, preceded only by Swiss, Singapore and Sweden, even though facing unstable global economic situations and the European debt crisis. Hence, observing the reasons why Finland’s industries have so strong innovative power, it seems to be related to the Finland’s national technology administrative system, and is worthy to be researched.

II. The Recent Situation of Finland’s Technology Administrative System

A. Preface

Finland’s administrative system is semi-presidentialism, and its executive power is shared by the president and the Prime Minister; as to its legislative power, is shared by the Congress and the president. The president is the Finland’s leader, and he/she is elected by the Electoral College, and the Prime Minister is elected by the Congress members, and then appointed by the president. To sum up, comparing to the power owned by the Prime Minister and the president in the Finland’s administrative system, the Prime Minister has more power upon executive power. So, actually, Finland can be said that it is a semi-predisnetialism country, but trends to a cabinet system.

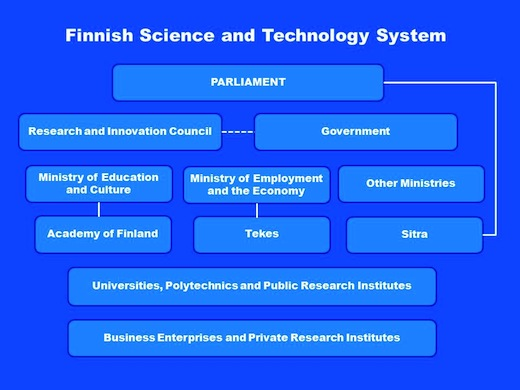

Finland technology administrative system can be divided into four parts, and the main agency in each part, based upon its authority, coordinates and cooperates with making, subsidizing, executing of Finland’s technology policies. The first part is the policy-making, and it is composed of the Congress, the Cabinet and the Research and Innovation Council; the second part is policy management and supervision, and it is leaded by the Ministry of Education and Culture, the Ministry of Employment and the Economy, and other Ministries; the third part is science program management and subsidy, and it is composed of the Academy of Finland (AOF), the National Technology Agency (Tekes), and the Finnish National Fund Research and Development (SITRA); the fourth part is policy-executing, and it is composed of universities, polytechnics, public-owned research institutions, private enterprises, and private research institutions. Concerning the framework of Finland’s technology administrative, it can be referred to below.

B. The Agency of Finland’s Technology Policy Making and Management

(A) The Agency of Finland’s Technology Policy Making

Finland’s technology policies are mainly made by the cabinet, and it means that the cabinet has responsibilities for the master plan, coordinated operation and fund-assignment of national technology policies. The cabinet has two councils, and those are the Economic Council and the Research and Innovation Council, and both of them are chaired by the Prime Minister. The Research and Innovation Council is reshuffled by the Science and Technology Policy Council (STPC) in 1978, and it changed name to the Research and Innovation Council in Jan. 2009. The major duties of the Research and Innovation Council include the assessment of country’s development, deals with the affairs regarding science, technology, innovative policy, human resource, and provides the government with aforementioned schedules and plans, deals with fund-assignment concerning public research development and innovative research, coordinates with all government’s activities upon the area of science, technology, and innovative policy, and executes the government’s other missions.

The Research and Innovation Council is an integration unit for Finland’s national technology policies, and it originally is a consulting agency between the cabinet and Ministries. However, in the actual operation, its scope of authority has already covered coordination function, and turns to direct to make all kinds of policies related to national science technology development. In addition, the consulting suggestions related to national scientific development policies made by the Research and Innovation Council for the cabinet and the heads of Ministries, the conclusion has to be made as a “Key Policy Report” in every three year. The Report has included “Science, Technology, Innovation” in 2006, “Review 2008” in 2008, and the newest “Research and Innovation Policy Guidelines for 2011-2015” in 2010.

Regarding the formation and duration of the Research and Innovation Council, its duration follows the government term. As for its formation, the Prime Minister is a chairman of the Research and Innovation Council, and the membership consists of the Minister of Education and Science, the Minister of Economy, the Minister of Finance and a maximum of six other ministers appointed by the Government. In addition to the Ministerial members, the Council shall comprise ten other members appointed by the Government for the parliamentary term. The Members must comprehensively represent expertise in research and innovation. The structure of Council includes the Council Secretariat, the Administrative Assistant, the Science and Education Subcommittee, and the Technology and Innovation Subcommittee. The Council has the Science and Education Subcommittee and the Technology and Innovation Subcommittee with preparatory tasks. There are chaired by the Ministry of Education and Science and by the Minister of Economy, respectively. The Council’s Secretariat consists of one full-time Secretary General and two full-time Chief Planning Officers. The clerical tasks are taken care of at the Ministry of Education and Culture.

(B) The Agency of Finland’s Technology Policy Management

The Ministries mainly take the responsibility for Finland’s technology policy management, which includes the Ministry of Education and Culture, the Ministry of Employment and Economy, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Transport and Communication, the Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Financial, and the Ministry of Justice. In the aforementioned Ministries, the Ministry of Education and Culture and the Ministry of Employment and Economy are mainly responsible for Finland national scientific technology development, and take charge of national scientific policy and national technical policy, respectively. The goal of national scientific policy is to promote fundamental scientific research and to build up related scientific infrastructures; at the same time, the authority of the Ministry of Education and Culture covers education and training, research infrastructures, fundamental research, applied research, technology development, and commercialization. The main direction of Finland’s national scientific policy is to make sure that scientific technology and innovative activities can be motivated aggressively in universities, and its objects are, first, to raise research funds and maintain research development in a specific ratio; second, to make sure that no matter on R&D institutions or R&D training, it will reach fundamental level upon funding or environment; third, to provide a research network for Finland, European Union and global research; fourth, to support the research related to industries or services based upon knowledge-innovation; fifth, to strengthen the cooperation between research initiators and users, and spread R&D results to find out the values of commercialization, and then create a new technology industry; sixth, to analyze the performance of national R&D system.

As for the Ministry of Employment and Economy, its major duties not only include labor, energy, regional development, marketing and consumer policy, but also takes responsibilities for Finland’s industry and technical policies, and provides industries and enterprises with a well development environment upon technology R&D. The business scope of the Ministry of Employment and Economy puts more focus on actual application of R&D results, it covers applied research of scientific technology, technology development, commercialization, and so on. The direction of Finland’s national technology policy is to strengthen the ability and creativity of industries’ technology development, and its objects are, first, to develop the new horizons of knowledge with national innovation system, and to provide knowledge-oriented products and services; second, to promote the efficiency of the government R&D funds; third, to provide cross-country R&D research networks, and support the priorities of technology policy by strengthening bilateral or multilateral cooperation; fourth, to raise and to broaden the efficiency of research discovery; fifth, to promote the regional development by technology; sixth, to evaluate the performance of technology policy; seventh, to increase the influence of R&D on technological change, innovation and society; eighth, to make sure that technology fundamental structure, national quality policy and technology safety system will be up to international standards.

(C) The Agency of Finland’s Technology Policy Management and Subsidy

As to the agency of Finland’s technology policy management and subsidy, it is composed of the Academy of Finland (AOF), the National Technology Agency (Tekes), and the Finnish National Fund Research and Development (SITRA). The fund of AOF comes from the Ministry of Education and Culture; the fund of Tekes comes from the Ministry of Employment and Economy, and the fund of SITRA comes from independent public fund supervised by the Finland’s Congress.

(D) The Agency of Finland’s Technology Plan Execution

As to the agency of Finland’s technology plan execution, it mainly belongs to the universities under Ministries, polytechnics, national technology research institutions, and other related research institutions. Under the Ministry of Education and Culture, the technology plans are executed by 16 universities, 25 polytechnics, and the Research Institute for the Language of Finland; under the Ministry of Employment and Economy, the technology plans are executed by the Technical Research Centre of Finland (VTT), the Geological Survey of Finnish, the National Consumer Research Centre; under the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, the technology plans are executed by the National Institute for Health and Welfare, the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, and University Central Hospitals; under the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, the technology plans are executed by the Finnish Forest Research Institute (Metla), the Finnish Geodetic Institute, and the Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute (RKTL); under the Ministry of Defense, the technology plans are executed by the Finnish Defense Forces’ Technical Research Centre (Pvtt); under the Ministry of Transport and Communications, the technology plans are executed by the Finnish Meteorological Institute; under the Ministry of Environment, the technology plans are executed by the Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE); under the Ministry of Financial, the technology plans are executed by the Government Institute for Economic Research (VATT). At last, under the Ministry of Justice, the technology plans are executed by the National Research Institute of Legal Policy.

Legal Analysis of the U.S. BIOSECURE Act: Implications for Taiwanese Biotechnology Companies 2024/11/15 I.Introduction The U.S. BIOSECURE Act (H.R.8333)[1](hereunder, "BIOSECURE Act" or "Act") is a strategic legislative measure designed to protect U.S. biotechnology technologies and data from potential exploitation by foreign entities deemed to be threats to national security. Passed by the House of Representatives on September 9, 2024, with a vote of 306-81[2], the Act demonstrates robust bipartisan support to limit foreign influence in critical U.S. sectors. Passed during the legislative session known as "China Week[3]," the Act imposes restrictions on government contracts, funding, and technological cooperation with entities classified as "Biotechnology Companies of Concern" (hereunder, "BCCs") that are affiliated with adversarial governments. Given Taiwan's prominent role in biotechnology and its strong trade ties with the U.S., Taiwanese companies must examine the implications of the BIOSECURE Act, specifically in regard to technology acquisition from restricted foreign companies and compliance obligations for joint projects with U.S. partners. This analysis will delve into three core aspects of the BIOSECURE Act: (1) the designation and evaluation of BCCs, (2) prohibitions on transactions involving BCCs, and (3) enforcement mechanisms. Each section will evaluate potential impacts on Taiwanese companies, focusing on how the Act might influence technology transfers, compliance obligations, and partnership opportunities within the U.S. biotechnology supply chain. II.Designation and Evaluation of Biotechnology Companies of Concern A central element of the BIOSECURE Act is the process of identifying and evaluating foreign biotechnology companies considered potential threats to U.S. national security.[4] Under Section 2(f)(2) of the Act, a "Biotechnology Company of Concern" is defined as any entity associated with adversarial governments—specifically, China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran[5]—that engages in activities or partnerships posing risks to U.S. security[6]. These risks may include collaboration with foreign military or intelligence agencies, involvement in dual-use research, or access to sensitive personal or genetic information of U.S. citizens. Companies already designated as BCCs include BGI, MGI, Complete Genomics, WuXi AppTec, and WuXi Biologics, all of which have substantial ties to China and the Chinese government or military[7]. Under Section 2(f)(4) of the Act, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is required to continuously evaluate and update the BCC list in consultation with agencies such as the Department of Defense, Department of Commerce, and the National Intelligence Community to reflect evolving security concerns[8]. The designation process presents significant challenges for Taiwanese companies, particularly those that have connections with BCCs or rely on BCC technologies for their products, diagnostics, or research initiatives. For instance, if a Taiwanese company uses gene sequencing technology or multiomics tools sourced from one of the designated BCCs, it may face restrictions when pursuing contracts with U.S. entities or seeking federal funding. To proactively address these challenges, Taiwanese companies should establish compliance protocols that verify the origin of their technology and data sources. Moreover, developing new supply chain relationships with U.S. or European suppliers may not only reduce reliance on BCC-affiliated technology but also enhance Taiwanese companies' reputation as secure and reliable partners in the biotechnology industry. By adapting proactively to the BCC designation process, Taiwanese companies can anticipate and respond to future regulatory shifts more effectively. Diversifying their technology base away from BCCs positions these companies to better align with U.S. biosecurity standards, thereby becoming more attractive collaborators for U.S.-based biotechnology and life sciences companies. Given the rapid pace of regulatory and security developments, staying informed about changes in BCC designations will enable Taiwanese companies to operate with greater agility, adjusting suppliers and adopting new compliance measures as needed. Such proactive alignment can strengthen their resilience and reinforce their status as stable and secure participants in the global biotechnology landscape. III.Prohibition on Government Contracts and Funding A core component of the BIOSECURE Act is its stringent restrictions on contracting and funding involving entities linked to BCCs, as detailed in Section 2(a) of the act[9]. These restrictions extend beyond direct federal interactions to include any recipients of federal funds, prohibiting them from using such funds to procure biotechnology products or services from BCCs[10]. By curtailing federal support and preventing indirect financial benefits to these companies, the U.S. aims to mitigate national security risks posed by adversarial governments. The wide-reaching scope of these prohibitions makes the BIOSECURE Act one of the most comprehensive legislative efforts to secure the biotechnology sector and address concerns over foreign technologies potentially compromising U.S. security interests. For Taiwanese biotechnology companies, these prohibitions introduce substantial compliance demands, particularly for companies that utilize BCC technology within their supply chains. For example, a Taiwanese company engaged in a joint research project with a U.S. government contractor may be required to demonstrate that none of its technology or data sources originate from BCCs. Compliance could necessitate rigorous supply chain audits and operational adjustments, potentially increasing short-term costs. However, aligning with U.S. regulatory standards preemptively can position Taiwanese companies as more desirable partners for U.S. entities that are increasingly prioritizing security and regulatory adherence. The BIOSECURE Act also incentivizes Taiwanese companies to explore alternative technology providers that meet U.S. biosecurity criteria, including secure data management practices, compliance with federal regulations, and the absence of connections to adversarial governments. By sourcing technology from approved U.S. or European biotechnology companies, Taiwanese companies can enhance their market access and collaborative prospects in the U.S. biotechnology and life sciences sectors. This strategy may also foster long-term stability in partnerships and mitigate risks associated with supply chain disruptions, particularly if more companies are designated as BCCs in the future[11]. Establishing partnerships with U.S.-aligned suppliers can also provide Taiwanese companies with a competitive edge in securing government contracts and research funding, as U.S.-based entities increasingly prefer suppliers that comply with national biosecurity requirements. IV.Enforcement Mechanisms, Transition Periods, and Taiwanese Considerations The BIOSECURE Act outlines key enforcement mechanisms and transitional provisions designed to facilitate the adjustment process for companies affected by its restrictions. Specifically, Section 2(c) of the Act provides an eight-year grandfathering period for contracts established prior to the Act’s effective date involving existing BCCs, allowing these agreements to continue until January 1, 2032[12]. This provision is intended to provide companies that are dependent on BCC-supplied biotechnology ample time to transition to compliant suppliers. In addition, the Act includes a "safe harbor" provision[13], which clarifies that equipment previously produced by a BCC but now sourced from a non-BCC entity will not be restricted. This allows companies to re-source components without the risk of penalties for past procurement decisions. For Taiwanese companies, this transition period presents a critical opportunity to adapt to the new regulatory environment without facing immediate disruptions to business operations. Companies dependent on BCC technology for essential biotechnological functions can leverage the eight-year window to gradually phase out such suppliers, thereby minimizing the impact on operations while ensuring future compliance. For example, a Taiwanese company that relies on a BCC’s sequencing technology for genomic research can use this period to forge partnerships with compliant technology suppliers, thereby avoiding sudden disruptions in research or production. Additionally, the Act includes a waiver provision[14] that allows case-by-case exemptions under specific conditions, particularly when compliance is infeasible, such as in instances where critical healthcare services abroad are at risk[15]. By making strategic use of the phased enforcement and waiver provisions, Taiwanese companies can restructure their supply chains to align fully with U.S. requirements. Those that plan these transitions carefully not only ensure regulatory compliance but also enhance their appeal as resilient and trustworthy partners in the U.S. market. Exploring new collaborations with U.S.-approved biotechnology suppliers can further bolster supply chain resilience against future geopolitical or regulatory uncertainties. The transition period[16] and waiver options[17] reflect the BIOSECURE Act's balanced approach between immediate security needs and pragmatic implementation, which Taiwanese companies can capitalize on to build robust, compliant biotechnological operations. V.Conclusion The U.S. BIOSECURE Act[18] presents both significant challenges and strategic opportunities for Taiwanese biotechnology companies. The Act’s restrictions on contracts with designated BCCs and funding constraints necessitate a reassessment of technology acquisition strategies and a reinforcement of compliance practices. Taiwanese companies seeking deeper integration into U.S. and global biotechnology markets will benefit from aligning their procurement approaches with non-BCC suppliers, particularly those in the U.S. or allied countries. This proactive alignment will not only mitigate potential compliance risks but also enhance Taiwanese companies’ reputations as reliable global partners in biotechnology. The phased enforcement and waiver provisions of the BIOSECURE Act[19] provide Taiwanese companies with a clear pathway to navigate the evolving regulatory landscape, allowing them to establish stronger, more resilient supply chains that meet U.S. standards. Such alignment positions these companies as competitive players in the biotechnology sector, contributing to secure and innovative progress in an increasingly interconnected world. By actively engaging with the BIOSECURE Act’s compliance demands, Taiwanese biotechnology companies can leverage the Act's phased implementation to ensure sustained, secure access to the U.S. market and foster strategic biotechnology partnerships. Reference: [1] U.S. CONGRESS, H.R. 8333 – U.S. BIOSECURE Act (2024), https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/8333 (last visited Nov. 1, 2024). [2] OFFICE OF THE CLERK, U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, Roll Call Vote No. 402 on H.R. 8333 (Sept. 9, 2024), https://clerk.house.gov/Votes?RollCallNum=402&BillNum=H.R.8333 (last visited Nov. 1, 2024). [3] JANINE LITTLE, U.S. House Of Representatives Passes The BIOSECURE Act During “China Week”, Global Supply Chain Law Blog (Sept. 13, 2024), https://www.globalsupplychainlawblog.com/supply-chain/u-s-house-of-representatives-passes-the-biosecure-act-during-china-week/ (last visited Nov. 1, 2024). [4] SABINE NAUGÈS & SARAH L. ENGLE, BIOSECURE Act: US Target on Chinese Biotechnology Companies, NAT'L L. REV. (Sept. 13, 2024), https://natlawreview.com/article/biosecure-act-us-target-chinese-biotechnology-companies (last visited Nov. 1, 2024). [5] 10 U.S.C. § 4872(d) (2024), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/10/4872 (last visited Nov. 1, 2024). [6] U.S. CONGRESS, H.R. 8333 – U.S. BIOSECURE Act (2024), https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/8333 (last visited Nov. 1, 2024). [7] id. [8] id. [9] id. [10] id. [11] JANINE LITTLE, U.S. House Of Representatives Passes The BIOSECURE Act During “China Week”, Global Supply Chain Law Blog (Sept. 13, 2024), https://www.globalsupplychainlawblog.com/supply-chain/u-s-house-of-representatives-passes-the-biosecure-act-during-china-week/ (last visited Nov. 1, 2024). [12] U.S. CONGRESS, H.R. 8333 – U.S. BIOSECURE Act (2024), https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/8333 (last visited Nov. 1, 2024). [13] id. [14] id. [15] id. [16] id. [17] id. [18] id. [19] id.

Israel’s Technological Innovation SystemI.Introduction Recently, many countries have attracted by Israel’s technology innovation, and wonder how Israel, resource-deficiency and enemies-around, has the capacity to enrich the environment for innovative startups, innovative R&D and other innovative activities. At the same time, several cross-border enterprises hungers to establish research centers in Israel, and positively recruits Israel high-tech engineers to make more innovative products or researches. However, there is no doubt that Israel is under the spotlight in the era of innovation because of its well-shaped national technology system framework, innovative policies of development and a high level of R&D expenditure, and there must be something to learn from. Also, Taiwanese government has already commenced re-organization lately, how to tightly connect related public technology sectors, and make the cooperation more closely and smoothly, is a critical issue for Taiwanese government to focus on. Consequently, by the observation of Israel’s national technology system framework and technology regulations, Israel’s experience shall be a valuable reference for Taiwanese government to build a better model for public technology sectors for future cooperation. Following harsh international competition, each country around the world is trying to find out the way to improve its ability to upgrade international competitiveness and to put in more power to promote technology innovation skills. Though, while governments are wondering how to strengthen their countries’ superiority, because of the differences on culture and economy, those will influence governments’ points of view to form an appropriate national innovative system, and will come with a different outcome. Israel, as a result of the fact that its short natural resources, recently, its stunning performance on technology innovation system makes others think about whether Israel has any characteristics or advantages to learn from. According to Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics records, Israel’s national expenditures on civilian R&D in 2013 amounted to NIS 44.2 billion, and shared 4.2% of the GDP. Compared to 2012 and 2011, the national expenditure on civilian R&D in 2013, at Israel’s constant price, increased by 1.3%, following an increase of 4.5% in 2012 and of 4.1% in 2011. Owing to a high level of national expenditure poured in, those, directly and indirectly, makes the outputs of Israel’s intellectual property and technology transfer have an eye-catching development and performance. Based on Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics records, in 2012-2013, approximately 1,438 IP invention disclosure reports were submitted by the researchers of various universities and R&D institutions for examination by the commercialization companies. About 1,019 of the reports were by companies at the universities, an increase of 2.2% compared to 2010-2011, and a 1% increase in 2010-2011 compared to 2008-2009. The dominant fields of the original patent applicants were medicines (24%), bio-technology (17%), and medical equipment (13%). The revenues from sales of intellectual property and gross royalties amounted to NIS 1,881 million in 2012, compared to NIS 1,680 million in 2011, and increase of 11.9%. The dominant field of the received revenues was medicines (94%). The revenues from sales of intellectual property and gross royalties in university in 2012 amounted to NIS 1,853 million in 2012, compared to NIS 1,658 million in 2011, an increase of 11.8%. Therefore, by the observation of these records, even though Israel only has 7 million population, compared to other large economies in the world, it is still hard to ignore Israel’s high quality of population and the energy of technical innovation within enterprises. II.The Recent Situation of Israel’s Technology Innovation System A.The Determination of Israel’s Technology Policy The direction and the decision of national technology policy get involved in a country’s economy growth and future technology development. As for a government sector deciding technology policy, it would be different because of each country’s government and administrative system. Compared to other democratic countries, Israel is a cabinet government; the president is the head of the country, but he/she does not have real political power, and is elected by the parliament members in every five years. At the same time, the parliament is re-elected in every four years, and the Israeli prime minister, taking charge of national policies, is elected from the parliament members by the citizens. The decision of Israel’s technology policy is primarily made by the Israeli Ministers Committee for Science and Technology and the Ministry of Science and Technology. The chairman of the Israeli Ministry Committee for Science and Technology is the Minister of Science and Technology, and takes charge of making the guideline of Israel’s national technology development policy and is responsible for coordinating R&D activities in Ministries. The primary function of the Ministry of Science and Technology is to make Israel’s national technology policies and to plan the guideline of national technology development; the scope includes academic research and applied scientific research. In addition, since Israel’s technology R&D was quite dispersed, it means that the Ministries only took responsibilities for their R&D, this phenomenon caused the waste of resources and inefficiency; therefore, Israel government gave a new role and responsibility for the Chief Scientists Forum under the Ministry of Science and Technology in 2000, and wished it can take the responsibility for coordinating R&D between the government’s sectors and non-government enterprises. The determination of technology policy, however, tends to rely on counseling units to provide helpful suggestions to make technology policies more intact. In the system of Israel government, the units playing a role for counseling include National Council for Research and Development (NCRD), the Steering Committee for Scientific Infrastructure, the National Council for Civil Research and Development (MOLMOP), and the Chief Scientists Forums in Ministries. Among the aforementioned units, NCRD and the Steering Committee for Scientific Infrastructure not only provide policy counseling, but also play a role in coordinating R&D among Ministries. NCRD is composed by the Chief Scientists Forums in Ministries, the chairman of Planning and Budgeting Committee, the financial officers, entrepreneurs, senior scientists and the Dean of Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. NCRD’s duties include providing suggestions regarding the setup of R&D organizations and related legal system, and advices concerning how to distribute budgets more effectively; making yearly and long-term guidelines for Israel’s R&D activities; suggesting the priority area of R&D; suggesting the formation of necessary basic infrastructures and executing the priority R&D plans; recommending the candidates of the Offices of Chief Scientists in Ministries and government research institutes. As for the Steering Committee for Scientific Infrastructure, the role it plays includes providing advices concerning budgets and the development framework of technology basic infrastructures; providing counsel for Ministries; setting up the priority scientific plans and items, and coordinating activities of R&D between academic institutes and national research committee. At last, as for MOLMOP, it was founded by the Israeli parliament in 2002, and its primary role is be a counseling unit regarding technology R&D issues for Israel government and related technology Ministries. As for MOLMOP’s responsibilities, which include providing advices regarding the government’s yearly and long-term national technology R&D policies, providing the priority development suggestion, and providing the suggestions for the execution of R&D basic infrastructure and research plans. B.The Management and Subsidy of Israel’s Technology plans Regarding the institute for the management and the subsidy of Israel’s technology plans, it will be different because of grantee. Israel Science Foundation (ISF) takes responsibility for the subsidy and the management of fundamental research plans in colleges, and its grantees are mainly focused on Israel’s colleges, high education institutes, medical centers and research institutes or researchers whose areas are in science and technical, life science and medicine, and humanity and social science. As for the budget of ISF, it mainly comes from the Planning and Budgeting Committee (PBC) in Israel Council for Higher Education. In addition, the units, taking charge of the management and the subsidy of technology plans in the government, are the Offices of the Chief Scientist in Ministries. Israel individually forms the Office of the Chief Scientist in the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Ministry of Communications, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of National Infrastructures, Energy and Water Resources, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Economy. The function of the Office of the Chief Scientist not only promotes and inspires R&D innovation in high technology industries that the Office the Chief Scientist takes charge, but also executes Israel’s national plans and takes a responsibility for industrial R&D. Also, the Office of the Chief Scientist has to provide aid supports for those industries or researches, which can assist Israel’s R&D to upgrade; besides, the Office of the Chief Scientists has to provide the guide and training for enterprises to assist them in developing new technology applications or broadening an aspect of innovation for industries. Further, the Office of the Chief Scientists takes charge of cross-country R&D collaboration, and wishes to upgrade Israel’s technical ability and potential in the area of technology R&D and industry innovation by knowledge-sharing and collaboration. III.The Recent Situation of the Management and the Distribution of Israel’s Technology Budget A.The Distribution of Israel’s Technology R&D Budgets By observing Israel’s national expenditures on civilian R&D occupied high share of GDP, Israel’s government wants to promote the ability of innovation in enterprises, research institutes or universities by providing national resources and supports, and directly or indirectly helps the growth of industry development and enhances international competitiveness. However, how to distribute budgets appropriately to different Ministries, and make budgets can match national policies, it is a key point for Israel government to think about. Following the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics records, Israel’s technology R&D budgets are mainly distributed to some Ministries, including the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Economy, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Ministry of National Infrastructures, Energy and Water Resources, the Israel Council for Higher Education and other Ministries. As for the share of R&D budgets, the Ministry of Science and Technology occupies the share of 1.7%, the Ministry of Economy is 35%, the Israel Council for Higher Education is 45.5%, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development is 8.15%, the Ministry of National Infrastructures, Energy and Water Resources is 1.1%, and other Ministries are 7.8% From observing that Israel R&D budgets mainly distributed to several specific Ministries, Israel government not only pours in lot of budgets to encourage civilian technology R&D, to attract more foreign capitals to invest Israel’s industries, and to promote the cooperation between international and domestic technology R&D, but also plans to provide higher education institutes with more R&D budgets to promote their abilities of creativity and innovation in different industries. In addition, by putting R&D budgets into higher education institutes, it also can indirectly inspire students’ potential innovation thinking in technology, develop their abilities to observe the trend of international technology R&D and the need of Israel’s domestic industries, and further appropriately enhance students in higher education institutes to transfer their knowledge into the society. B.The Management of Israel’s Technology R&D Budgets Since Israel is a cabinet government, the cabinet takes responsibility for making all national technology R&D policies. The Ministers Committee for Science and Technology not only has a duty to coordinate Ministries’ technology policies, but also has a responsibility for making a guideline of Israel’s national technology development. The determination of Israel’s national technology development guideline is made by the cabinet conference lead by the Prime Minister, other Ministries does not have any authority to make national technology development guideline. Aforementioned, Israel’s national technology R&D budgets are mainly distributed to several specific Ministries, including the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Economy, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Ministry of National Infrastructures, Energy and Water Resources, the Israel Council for Higher Education, and etc. As for the plan management units and plan execution units in Ministries, the Office of the Chief Scientist is the plan management unit in the Ministry of Science and Technology, and Regional Research and Development Centers is the plan execution unit; the Office of the Chief Scientist is the plan management unit in the Ministry of Economy, and its plan execution unit is different industries; the ISF is the plan management units in the Israel Council for Higher Education; also, the Office of the Chief Scientist is the plan management unit in the Ministry of Agriculture, and its plan execution units include the Institute of Field and Garden Corps, the Institute of Horticulture, the Institute of Animal, the Institute of Plan Protection, the Institute of Soil, Water & Environmental Sciences, the Institute for Technology and Storage of Agriculture Products, the Institute of Agricultural Engineering and Research Center; the Office of the Chief Scientist is the plan management unit in the Ministry of National Infrastructures, Energy and Water Resources, and its plan execution units are the Geological Survey of Israel, Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research and the Institute of Earth and Physical. As for other Ministries, the Offices of the Chief Scientist are the plan management units for Ministries, and the plan execution unit can take Israel National Institute for Health Policy Research or medical centers for example.

Legal Opinion Led to Science and Technology Law: By the Mechanism of Policy Assessment of Industry and Social NeedsWith the coming of the Innovation-based economy era, technology research has become the tool of advancing competitive competence for enterprises and academic institutions. Each country not only has begun to develop and strengthen their competitiveness of industrial technology but also has started to establish related mechanism for important technology areas selected or legal analysis. By doing so, they hope to promote collaboration of university-industry research, completely bring out the economic benefits of the R & D. and select the right technology topics. To improve the depth of research cooperation and collect strategic advice, we have to use legislation system, but also social communication mechanism to explore the values and practical recommendations that need to be concerned in policy-making. This article in our research begins with establishing a mechanism for collecting diverse views on the subject, and shaping more efficient dialogue space. Finally, through the process of practicing, this study effectively collects important suggestions of practical experts.

Introduction to the “Public Procurement for Startups” mechanismIntroduction to the “Public Procurement for Startups” mechanism I.Backgrounds According to the EU’s statistics, government procurement budget accounted for over 14% of GDP. And, according to the media report, the total amount of government procurement in Taiwan in 2017 accounted for nearly 8%. Therefore, the government’s procurement power has gradually become a policy tool for the government to promote the development of innovative products and services. In 2017, the Executive Yuan of the R.O.C.(Taiwan)announced a government procurement policy named “Government as Good Partners with Startups (政府成為新創好夥伴)”[1] to encourage government agencies and State-owned Enterprises to procure and adopt innovative goods or services provided by startups. This policy was subsequently implemented through an action plan named “Public Procurement for Startups”(新創採購)[2] by the Small and Medium Enterprise Administration(SMEA).The action plan mainly includes two important parts:One created the procurement process for startups to enter the government contracts market through inter-entities contracts. The other accelerated the collaboration of the government agencies and startups through empirical demonstration. II.Facilitating the procurement process for startups to enter the government market In order to help startups enter the government contracts market in a more efficient way, the SMEA conducts the procurement of inter-entity supply contracts with suppliers, especially startups, for the supply of innovative goods or services. An inter-entity supply contract[3] is a special contractual framework, under which the contracting entity on behalf of two or more other contracting parties signs a contract with suppliers and formulates the specifics and price of products or services provided through the public procurement process. Through the process of calling for tenders, price competition and so on, winning tenderers will be selected and listed on the Government E-Procurement System. This framework allows those contracting entities obtain orders and acquire products or services which they need in a more efficient way so it increases government agencies’ willingness to procure and use innovative products and services. From 2018, the SMEA started to undertake the survey of innovative products and services that government agencies usually needed and conducted the procurement of inter-entity supply contracts for two rounds every year. As a result, the SMEA plays an important role to bridge the demand and supply sides for innovative products or services by means of implementing the forth-mentioned survey and procurement process. Moreover, in order to explore more innovative products and services with high quality and suitable for government agencies and public institutions, the SMEA actively networked with various stakeholders, including incubators, accelerators, startups mentoring programs sponsored by private and public sectors and so on. Initially the items to be procured were categorized into four themes which were named the Smart Innovations, the Smart Eco, the Smart Healthcare, and the Smart Security. Later, in order to show the diversity of the innovation of startups which response well to various social issues, from 2019, the SMEA introduced two new theme solicitations titled the Smart Education and the Smart Agriculture to the inter-entities contracts. Those items included the power management systems, the AI automated recognition and image warning system, the chatbot for public service, unmanned flying vehicles, aerial photography services and so on. Take the popular AI image warning system as an example, the system is used by police officers to make instant evidence searching and image recording. Other government agencies apply the innovative system to the investigation of illegal logging and school safety surveillance. Moreover, the SMEA has also offered subsidy for local governments tobuy those items provided by startups. That is the coordinated supporting measure which allows startups the equal playing field to compete with large companies. The Subsidy scheme is based on the Guideline for Subsidies on Procurement of Innovative Products and Services[3] (approved by the Executive Yuan on March 29, 2018 and revised on Feb. 20, 2021). In the Guideline, “innovative products and services” refer to the products, technologies, labor, service flows or items and services rendered with creative activities through deploying scientific or technical means and a certain degree of innovations by startups with less than five years in operation. Such innovative products and services are displayed for the inter-entity supply contractual framework administered by the SMEA for government procurement. III.Accelerating the collaboration of the government agencies and startups through empirical demonstration To assist startups to prove their concepts or services, and become more familiar with the governemnrt’s needs, the SMEA also created a mechanism called the “Solving Governmental Problems by Star-up Innovation”(政府出題˙新創解題). It plans to collect government agencies’ needs, and then solicit innovative proposals from startups. After their proposals are accepted, startups will be given a grant up to one million NT dollars to conduct empirical studies on solution with government agencies for about half a year. Take the cooperation between the “Taoyuan Long Term Care Institute for Older People and the Biotech Startup” for example, a care system with sanitary aids was introduced to provide automatic detection, cleanup and dry services for the patients’discharges, thus saving 95% of cleaning time for caregivers. In the past, caregivers usually spent 4 hours on the average in inspecting old patients, cleaning and replacing their bedsheets as their busy daily routines. Inadequate caregivers makes it difficult to maintain the care quality. If the problem was not addressed immediately, it would make the life of old patients more difficult. IV.Achievements to date Since the promotion of the products and services of the startups and the launch of the “Public Procurement for Startups” program in 2018, 68 startups, with the SMEA’s assistance, have entered the government procurement contracts market, and more than 100 government agencies have adopted the innovative resolutions. With the encouragement for them in adopting and utilizing the fruits of the startups, it has generated more than NT$150 million in cooperative business opportunities. V.Conclusions While more and more startups are obtaining business opportunities from the favorable procurement process, constant innovation remains the key to success. As such, the SMEA has regularly visited the government agencies-buyers to obtain feedbacks from startups so as to adjust and optimize the innovative products or services. The SMEA has also regularly renewed the specifics and items of the procurement list every year to keep introducing and supplying high-quality products or services to the government agencies. Reference: [1] Policy for investment environment optimization for Startups(2017),available athttps://www.ndc.gov.tw/nc_27_28382.(last visited on July 30, 2021 ) [2] https://www.spp.org.tw/spp/(last visited on July 30, 2021 ) [3] Article 93 of Government Procurement Act:I An entity may execute an inter-entity supply contract with a supplier for the supply of property or services that are commonly needed by entities. II The regulations for a procurement of an inter-entity supply contract, the matters specified in the tender documentation and contract, applicable entities, and the related matters shall be prescribed by the responsible entity. [4] https://law.moea.gov.tw/LawContent.aspx?id=GL000555(last visited on July 30, 2021)

- Impact of Government Organizational Reform to Scientific Research Legal System and Response Thereto (1) – For Example, The Finnish Innovation Fund (“SITRA”)

- The Demand of Intellectual Property Management for Taiwanese Enterprises

- Blockchain in Intellectual Property Protection

- Impact of Government Organizational Reform to Research Legal System and Response Thereto (2) – Observation of the Swiss Research Innovation System

- Recent Federal Decisions and Emerging Trends in U.S. Defend Trade Secrets Act Litigation

- The effective and innovative way to use the spectrum: focus on the development of the "interleaved/white space"

- Copyright Ownership for Outputs by Artificial Intelligence

- Impact of Government Organizational Reform to Research Legal System and Response Thereto (2) – Observation of the Swiss Research Innovation System