Impact of Government Organizational Reform to Research Legal System and Response Thereto (2) – Observation of the Swiss Research Innovation System

Impact of Government Organizational Reform to Research Legal System and Response Thereto (2) – Observation of the Swiss Research Innovation System

I. Foreword

Switzerland is a landlocked country situated in Central Europe, spanning an area of 41,000 km2, where the Alps occupy 60% of the territory, while it owns little cultivated land and poor natural resources. In 2011, its population was about 7,950,000 persons[1]. Since the Swiss Federal was founded, it has been adhering to a diplomatic policy claiming neutrality and peace, and therefore, it is one of the safest and most stable countries in the world. Switzerland is famous for its high-quality education and high-level technological development and is very competitive in biomedicine, chemical engineering, electronics and metal industries in the international market. As a small country with poor resources, the Swiss have learnt to drive their economic and social development through education, R&D and innovation a very long time ago. Some renowned enterprises, including Nestle, Novartis and Roche, are all based in Switzerland. Meanwhile, a lot of creative small-sized and medium-sized enterprises based in Switzerland are dedicated to supporting the export-orientation economy in Switzerland.

Switzerland has the strongest economic strength and plentiful innovation energy. Its patent applications, publication of essay, frequencies of quotation and private enterprises’ innovation performance are remarkable all over the world. According to the Global Competitiveness Report released by the World Economic Forum (WEF), Switzerland has ranked first among the most competitive countries in the world for four years consecutively since 2009[2]. Meanwhile, according to the Global Innovation Index (GII) released by INSEAD and the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) jointly, Switzerland has also ranked first in 2011 and 2012 consecutively[3]. Obviously, Switzerland has led the other countries in the world in innovation development and economic strength. Therefore, when studying the R&D incentives and boosting the industrial innovation, we might benefit from the experience of Switzerland to help boost the relevant mechanism in Taiwan.

Taiwan’s government organization reform has been launched officially and boosted step by step since 2012. In the future, the National Science Council will be reformed into the “Ministry of Science and Technology”, and the Ministry of Economic Affairs into the “Ministry of Economy and Energy”, and the Department of Industrial Development into the “Department of Industry and Technology”. Therefore, Taiwan’s technology administrative system will be changed materially. Under the new government organizational framework, how Taiwan’s technology R&D and industrial innovation system divide work and coordinate operations to boost the continuous economic growth in Taiwan will be the first priority without doubt. Support of innovation policies is critical to promotion of continuous economic growth. The Swiss Government supports technological research and innovation via various organizations and institutions effectively. In recent years, it has achieved outstanding performance in economy, education and innovation. Therefore, we herein study the functions and orientation of the competent authorities dedicated to boosting research and innovation in Switzerland, and observe its policies and legal system applied to boost the national R&D in order to provide the reference for the functions and orientation of the competent authorities dedicated to boosting R&D and industrial innovation in Taiwan.

II. Overview of Swiss Federal Technology Laws and Technology Administrative System

Swiss national administrative organization is subject to the council system. The Swiss Federal Council is the national supreme administrative authority, consisting of 7 members elected from the Federal Assembly and dedicated to governing a Federal Government department respectively. Switzerland is a federal country consisting of various cantons that have their own constitutions, councils and governments, respectively, entitled to a high degree of independence.

Article 64 of the Swiss Federal Constitution[4] requires that the federal government support research and innovation. The “Research and Innovation Promotion Act” (RIPA)[5] is dedicated to fulfilling the requirements provided in Article 64 of the Constitution. Article 1 of the RIPA[6] expressly states that the Act is enacted for the following three purposes: 1. Promoting the scientific research and science-based innovation and supporting evaluation, promotion and utilization of research results; 2. Overseeing the cooperation between research institutions, and intervening when necessary; 3. Ensuring that the government funding in research and innovation is utilized effectively. Article 4 of the RIPA provides that the Act shall apply to the research institutions dedicated to innovation R&D and higher education institutions which accept the government funding, and may serve to be the merit for establishment of various institutions dedicated to boosting scientific research, e.g., the National Science Foundation and Commission of Technology & Innovation (CTI). Meanwhile, the Act also provides detailed requirements about the method, mode and restriction of the government funding.

According to the RIPA amended in 2011, the Swiss Federal Government’s responsibility for promoting innovation policies has been extended from “promotion of technology R&D” to “unification of education, research and innovation management”, making the Swiss national industrial innovation framework more well-founded and consistent[8] . Therefore, upon the government organization reform of Switzerland in 2013, most of the competent authorities dedicated to technology in Swiss have been consolidated into the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research.

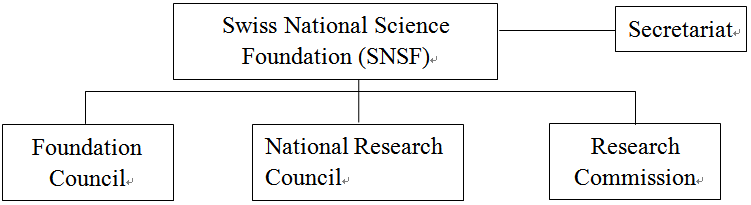

Under the framework, the Swiss Federal Government assigned higher education, job training, basic scientific research and innovation to the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI), while the Commission of Technology & Innovation (CTI) was responsible for boosting the R&D of application scientific technology and industrial technology and cooperation between the industries and academy. The two authorities are directly subordinate to the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research (EAER). The Swiss Science and Technology Council (SSTC), subordinate to the SERI is an advisory entity dedicated to Swiss technology policies and responsible for providing the Swiss Federal Government and canton governments with the advice and suggestion on scientific, education and technology innovation policies. The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) is an entity dedicated to boosting the basic scientific R&D, known as the two major funding entities together with CTI for Swiss technology R&D. The organizations, duties, functions and operations of certain important entities in the Swiss innovation system are introduced as following.

Date source: Swiss Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research official website

Fig. 1 Swiss Innovation Framework Dedicated to Boosting Industries-Swiss Federal Economic, Education and Research Organizational Chart

1. State Secretariat of Education, Research and Innovation (SERI)

SERI is subordinate to the Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research, and is a department of the Swiss Federal Government dedicated to managing research and innovation. Upon enforcement of the new governmental organization act as of January 1, 2013, SERI was established after the merger of the State Secretariat for Education and Research, initially subordinate to Ministry of Interior, and the Federal Office for Professional Education and Technology (OEPT), initially subordinated to Ministry of Economic Affairs. For the time being, it governs the education, research and innovation (ERI). The transformation not only integrated the management of Swiss innovation system but also unified the orientations toward which the research and innovation policy should be boosted.

SERI’s core missions include “enactment of national technology policies”, “coordination of research activities conducted by higher education institutions, ETH, and other entities of the Federal Government in charge of various areas as energy, environment, traffic and health, and integration of research activities conducted by various government entities and allocation of education, research and innovation resources. Its functions also extend to funding the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) to enable SNSF to subsidize the basic scientific research. Meanwhile, the international cooperation projects for promotion of or participation in research & innovation activities are also handled by SERI to ensure that Switzerland maintains its innovation strength in Europe and the world.

The Swiss Science and Technology Council (SSTC) is subordinate to SERI, and also the advisory unit dedicated to Swiss technology policies, according to Article 5a of RIPA[9]. The SSTC is responsible for providing the Swiss Federal Government and canton governments with advice and suggestion about science, education and innovation policies. It consists of the members elected from the Swiss Federal Council, and a chairman is elected among the members.

2. Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF)

The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) is one of the most important institutions dedicated to funding research, responsible for promoting the academic research related to basic science. It supports about 8,500 scientists each year. Its core missions cover funding as incentives for basic scientific research. It grants more than CHF70 million each year. Nevertheless, the application science R&D, in principle, does not fall in the scope of funding by the SNSF. The Foundation allocates the public research fund under the competitive funding system and thereby maintains its irreplaceable identity, contributing to continuous output of high quality in Switzerland.

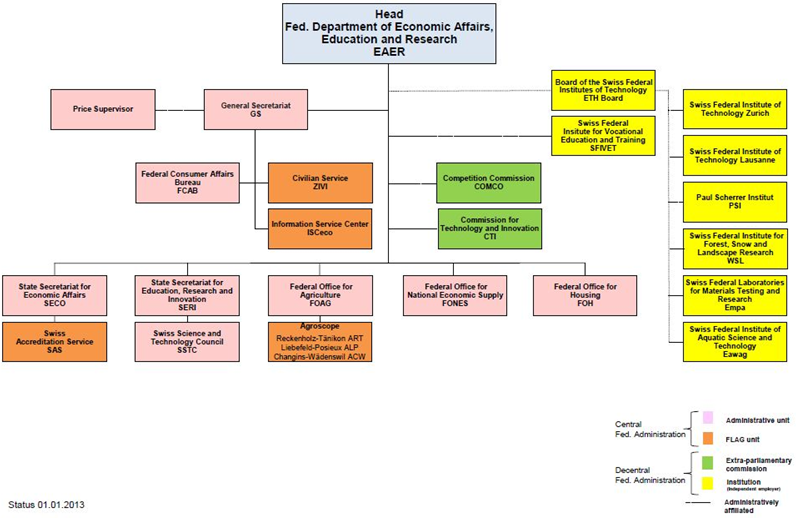

With the support from the Swiss Federal Government, the SNSF was established in 1952. In order to ensure independence of research, it was planned as a private institution when it was established[10]. Though the funding is provided by SERI, the SNSF still has a high degree of independence when performing its functions. The R&D funding granted by the SNSF may be categorized into the funding to free basic research, specific theme-oriented research, and international cooperative technology R&D, and the free basic research is granted the largest funding. The SNSF consists of Foundation Council, National Research Council and Research Commission[11].

Data source: prepared by the Study

Fig. 2 Swiss National Science Foundation Organizational Chart(1) Foundation Council

The Foundation Council is the supreme body of the SNSF[12], which is primarily responsible for making important decisions, deciding the role to be played by the SNSF in the Swiss research system, and ensuring SNSF’s compliance with the purpose for which it was founded. The Foundation Council consists of the members elected from the representatives from important research institutions, universities and industries in Swiss, as well as the government representatives nominated by the Swiss Federal Council. According to the articles of association of the SNSF[13], each member’s term of office should be 4 years, and the members shall be no more than 50 persons. The Foundation Council also governs the Executive Committee of the Foundation Council consisting of 15 Foundation members. The Committee carries out the mission including selection of National Research Council members and review of the Foundation budget.

(2) National Research Council

The National Research Council is responsible for reviewing the applications for funding and deciding whether the funding should be granted. It consists of no more than 100 members, mostly researchers in universities and categorized, in four groups by major[14], namely, 1. Humanities and Social Sciences; 2. Math, Natural Science and Engineering; 3. Biology and Medical Science; and 4. National Research Programs (NRPs)and National Centers of Competence in Research (NCCRs). The NRPs and NCCRs are both limited to specific theme-oriented research plans. The funding will continue for 4~5years, amounting to CHF5 million~CHF20 million[15]. The specific theme-oriented research is applicable to non-academic entities, aiming at knowledge and technology transfer, and promotion and application of research results. The four groups evaluate and review the applications and authorize the funding amount.

Meanwhile, the representative members from each group form the Presiding Board dedicated to supervising and coordinating the operations of the National Research Council, and advising the Foundation Council about scientific policies, reviewing defined funding policies, funding model and funding plan, and allocating funding by major.

(3) Research Commissions

Research Commissions are established in various higher education research institutions. They serve as the contact bridge between higher education academic institutions and the SNSF. The research commission of a university is responsible for evaluating the application submitted by any researcher in the university in terms of the school conditions, e.g., the school’s basic research facilities and human resource policies, and providing advice in the process of application. Meanwhile, in order to encourage young scholars to attend research activities, the research committee may grant scholarships to PhD students and post-doctor research[16].

~to be continued~

[1] SWISS FEDERAL STATISTICS OFFICE, Switzerland's population 2011 (2012), http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/en/index/news/publikationen.Document.163772.pdf (last visited Jun. 1, 2013).

[2] WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM [WEF], The Global Competiveness Report 2012-2013 (2012), http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2012-13.pdf (last visited Jun. 1, 2013); WEF, The Global Competiveness Report 2011-2012 (2011), http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GCR_Report_2011-12.pdf (last visited Jun. 1, 2013); WEF, The Global Competiveness Report 2010-2011 (2010), http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2010-11.pdf (last visited Jun. 1, 2013); WEF, The Global Competiveness Report 2009-2010 (2009),. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2009-10.pdf (last visited Jun. 1, 2013).

[3] INSEAD, The Global Innovation Index 2012 Report (2012), http://www.globalinnovationindex.org/gii/GII%202012%20Report.pdf (last visited Jun. 1, 2013); INSEAD, The Global Innovation Index 2011 Report (2011), http://www.wipo.int/freepublications/en/economics/gii/gii_2011.pdf (last visited Jun. 1, 2013).

[4] SR 101 Art. 64: “Der Bund fördert die wissenschaftliche Forschung und die Innovation.”

[5] Forschungs- und Innovationsförderungsgesetz, vom 7. Oktober 1983 (Stand am 1. Januar 2013). For the full text, please see www.admin.ch/ch/d/sr/4/420.1.de.pdf (last visited Jun. 3, 2013).

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] CTI, CTI Multi-year Program 2013-2016 7(2012), available at http://www.kti.admin.ch/?lang=en&download=NHzLpZeg7t,lnp6I0NTU042l2Z6ln1ad1IZn4Z2qZpnO2Yuq2Z6gpJCDeYR,hGym162epYbg2c_JjKbNoKSn6A-- (last visited Jun. 3, 2013).

[9] Supra note 5.

[10] Swiss National Science Foundation, http://www.snf.ch/E/about-us/organisation/Pages/default.aspx (last visited Jun. 3, 2013).

[11] Id.

[12] Foundation Council, Swiss National Science Foundation, http://www.snf.ch/E/about-us/organisation/Pages/foundationcouncil.aspx (last visited Jun. 3, 2013).

[13] See Statutes of Swiss National Science Foundation Art.8 & Art. 9, available at http://www.snf.ch/SiteCollectionDocuments/statuten_08_e.pdf (last visited Jun. 3, 2013).

[14] National Research Council, Swiss National Science Foundation, http://www.snf.ch/E/about-us/organisation/researchcouncil/Pages/default.aspx (last visted Jun.3, 2013).

[15] Theres Paulsen, VISION RD4SD Country Case Study Switzerland (2011), http://www.visionrd4sd.eu/documents/doc_download/109-case-study-switzerland (last visited Jun.6, 2013).

[16] Research Commissions, Swiss National Science Foundation, http://www.snf.ch/E/about-us/organisation/Pages/researchcommissions.aspx (last visted Jun. 6, 2013).

Adopting Flexible Mechanism to Promote Public Procurement of Innovation—the Amendment of Article 27 of the Statute for Industrial Innovation I.Introduction To further industrial innovation, improve industrial environment, and enhance industrial competitiveness through a systematic long-term approach, the Statute for Industrial Innovation (hereinafter referred to as the Statute) has been formulated in Taiwan. The central government authority of this Statute is the Ministry of Economic Affairs, and the Industrial Development Bureau of the Ministry of Economic Affairs (henceforth referred to as the IDB) is the administrative body for the formulation of this Statute. Since its formulation and promulgation in 2010, the Statute has undergone four amendments. The latest amendment, passed by the Legislative Yuan on November 3, 2017, on the third reading, is a precipitate of the international industrial development trends. The government is actively encouraging the investment in industrial innovation through a combination of capital, R&D, advanced technologies and human resources to help the promotion of industrial transformation, hence this large scale amendment is conducted. The amendment, promulgated and enacted on November 22, 2017, focuses on eight key points, which include: state-owned businesses partaking in R&D (Article 9-1 of the amended provisions of the Statute), the tax concessions of the limited partnership venture capital businesses (Article 2, Article 10, Article 12-1 and Article 23-1 of the amended provisions of the Statute), the tax concessions of Angel Investors (Article 23-2 of the amended provisions of the Statute), applicable tax deferral of employees' stock compensation (Article 19-1 of the amended provisions of the Statute), tax deferral benefit of stocks given to research institution creators (Article 12-2 of the amended provisions of the Statute), the promotion of flexible mechanism for innovation procurement (Article 27 of the amended provisions of the Statute), the establishment of evaluation mechanism for intangible assets (Article 13 of the amended provisions of the Statute), and forced sale auction of idled land for industrial use (Article 46-1 of the amended provisions of the Statute). This paper focuses on the amendment of Article 27 of the Fourth Revision of the Statute, which is also one of the major focuses of this revision—promoting flexible mechanism for innovation procurement, using the mass-market purchasing power of the government as the energetic force for the development of industrial innovation. II.Explanation of the Amendment of Article 27 of the Statute 1.Purposes and Descriptions of the Amendment of Article 27 of the Statute The original intent of Article 27 (hereinafter referred to as the Article) of the Statute, prior to the latest amendment (content of the original provisions is shown in Table 1), was to encourage government agencies and enterprises to give a priority to using green products through the "priority procurement" provisions of Paragraph 2, which allow government agencies to award contracts to green product producers using special government procurement procedures, so as to increase the opportunities for government agencies to use green products, and thereby promote the sustainable development of the industry. In view of the inherent tasks of promoting the development of industrial innovation, and considering that, using the large-scale government procurement demand to guide industrial innovation activities, has become the policy instrument accepted by most advanced countries, the IDB expects that, with the latest amendment of Article 27, the procurement mechanism policy for software, innovative products and services, in addition to the original green products, may become influential, and that "innovative products and services" may be included in the scope of "Priority Procurement" of this Article namely, make “priority procurement of innovative products and services” as one of the flexible mechanisms for promoting innovation procurement. A comparison of the amended provisions and the original provisions is shown in Table 1, and an explanation of the amendment is described as follows:[1] Table 1 A Comparison of Article 27 Amendment of the Statute for Industrial Innovation Amended Provisions Original Provisions Article 27 (I) Each central government authority in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry shall encourage government organizations (agencies) and enterprises to procure software, innovative and green products or services. (II) To enhance the procurement efficiencies, as effected by supply and demand, the central government authority shall offer assistance and services to the organizations (agencies) that handle these procurements as described in the preceding paragraph; wherein, Inter-entity Supply Contracts that are required for the aforesaid procurements, the common requirements shall be decided, in accordance with policy requirements, upon consultation between the central government authority and each central government authority in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry. (III) Where the software, innovative and green products or services, as described in Paragraph 1, must be tested, audited, accredited and certified, their associated fees and charges may be reduced, exempted, or suspended. (IV) Government organizations (agencies) may specify in the tender document the priority procurement of innovative and green products or services that have been identified to meet the requirements of paragraph 1. However, such a specification shall not violate treaties or agreements that have been ratified by the Republic of China. The measures concerning specifications, categories, and identification procedures of software, innovative and green products or services as prescribed in Paragraph 1; the testing, auditing criteria, accreditation and certification as prescribed in paragraph 3; and the Priority Procurement in paragraph 4 and other relevant items, shall be established by each central government authority in charge of end-enterprises of a specific industry. Article 27 (I) Each central government authority in charge of end enterprises shall encourage government agencies and enterprises to give priority to green products that are energy/resources recyclable/renewable, energy and water saving, non-toxic, less-polluting, or able to reduce the burden on the environment. (II) Agencies may specify in the tender documents that priority is given to green products meeting the requirement set forth in the preceding Paragraph. (III) The regulations governing the specifications, categories, certification procedures, review standards, and other relevant matters relating to the green products as referred to in the preceding Paragraph shall be prescribed by the central government authorities in charge of end enterprises. Source: The Ministry of Economic Affairs (I).Paragraph 1 In order to compel each central government authority in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry to motivate industrial innovation activities and sustainable development on the basis of requirements, and to support the development of the software industry in Taiwan, the provision, that such an authority should encourage government organizations (agencies) and enterprises to procure software and innovative products and services, is added in paragraph 1. (II).Paragraph 2 This procurement, as described in paragraph 1, is different from the property or services procurement of general affairs as handled by various organizations. To enhance procurement efficiencies, as effected by supply and demand, the central government authority, i.e., the Ministry of Economic Affairs, shall provide relevant assistance and services to organizations (agencies) handling these procurements, hence the added provisions in paragraph 2. For purchases using inter-entity supply contracts, which are bound by the requirements of this Article, due to their prospective nature, and that the common demand of each organization is difficult to make an accurate estimate by using a demand survey or other method, the Ministry of Economic Affairs shall discuss the issues with each central government authority in charge of end-enterprises of a specific industry, who consult or promote policies, and are in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry, and then make decisions in accordance with the policy promotion requirements. (III).Paragraph 3 The fee schedule for testing, auditing, accrediting and certifying software, innovative and green products or services is covered by Article 7, Administrative Fees of the Charges And Fees Act. The authorities in charge should determine relevant fee standards.However, considering that the test, audit, accreditation and certification may be conducted during a trial or promotional period, or circumstances dictate that it is necessary to motivate tenderer participation, the fee may be reduced, waived or suspended; hence, paragraph 3 is added. (IV).Paragraph 4 Paragraph 2 of the original provision is moved to paragraph 4 with the revisions made to paragraph 1, accordingly, and the provision for using Priority Procurement to handle innovative products or services is added. However, for organizations covered by The Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA), due to Taiwan's accession to the WTO, ANZTEC, and ASTEP, their procurement of items covered in the aforesaid agreements with a value reaching the legislated threshold, shall be handled in accordance with the regulations stipulated in the aforesaid agreements; hence the stipulation in the proviso that the procurement must not violate the provisions of treaties or agreements ratified by the Taiwan government. (V).Paragraph 5 Paragraph 3 of the original Article is moved to paragraph 5 with the revisions made to paragraph 1, accordingly, and the provision, that authorizes each central government authority in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry to determine appropriate measures concerning the methods of defining software, innovative and green products and services, as well as matters relating to test, accreditation, certification and priority procurement, is added. 2.The Focus of the Amendment of Article 27 of the Statute—Promoting a Flexible Mechanism for Innovation Procurement As previously stated, the amendment of this Article aims to stimulate activities of industrial innovation by taking advantage of the huge demand from government agencies. With the government agencies being the users of the innovative products or services, government's procurement market potential is tapped to support the development of industrial innovation. The original intention of amendment is to incorporate the spirit of Public Procurement of Innovation[2] into this Article, and to try to introduce EU's innovation procurement mechanism[3] into our laws. So that, a procurement procedure, that is more flexible and not subject to the limitation of procurement procedures currently stipulated by the Government Procurement Act, may be adopted to facilitate government sector action in taking the lead on adopting innovative products or services that have just entered their commercial prototype stage, or utilizing the demand for innovation in the government sector to drive industry's innovative ideas or R&D (that can not be satisfied with the existing solutions in the marketplace). However, while it is assessing the relevant laws and regulations of our government procurement system and the practice of implementation, the use of the current government procurement mechanism by organizations in the public sector to achieve the targets of innovation procurement is still in its infancy. It is difficult to achieve the goal, in a short time, of establishing a variety of Public Procurement of Innovation Solutions (PPI Solutions) as disclosed in the EU's Directive 2014/24 / EU, enacted by the EU in 2014, in ways that are not subject to current government procurement legislation. Hence, the next best thing: Instead of setting up an innovative procurement mechanism in such a way that it is "not subject to the restrictions of the current government procurement law", we will focus on utilizing the flexible room available under the current system of government procurement laws and regulations, and promoting the "flexible mechanism for innovation procurement” paradigm. With the provisions now provided in Article 27 of the Statute for Industrial Innovation, the government sector is authorized to adopt the "Priority Procurement" method on innovative products and services, thus increasing the public sector's access to innovative products and services. With this amendment, in addition to the "green products" listed in the original provisions of paragraph 1 of the Statute, "software" and "innovative products or services"[4] are now incorporated into the target procurement scope and each central government authority in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry should now encourage government organizations and enterprises to implement; however, the provisions of this paragraph do not have the specific effect of law, they are declaratory provisions. Two priorities are the1 primary focus of the provisions of paragraph 2 and paragraph 4 of this Article for promoting flexible mechanism for innovation procurement: (I)The procurement of software, innovative and green products or services that uses Inter-entity Supply Contracts may rely on the "policy requirement" to establish the common demand. According to the first half of the provisions of paragraph 2 of this Article, the Ministry of Economic Affairs, being the central government authority of the Statute, may provide assistance and services to organizations dealing with the procurement of software, innovative and green products and services.This is because the procurement subjects, as pertaining to software, products or services that are innovative and green products (or services), usually have the particularities (especially in the software) of the information professions; different qualities (especially in innovative products or services), and are highly profession-specific. They are different from the general affairs goods and services procured by most government agencies. Hence, the Ministry of Economic Affairs may provide assistance and service to these procurement agencies, along with the coordination of relevant organizations, in matters relating to the aforesaid procurement process in order to improve procurement efficiency as relates to supply and demand. Pursuant to the second half of Paragraph 2 of this Article, if the inter-entity supply contract method is used to process the procurement of software, innovative products and services, green products (or services) and other related subjects, there could be "Commonly Required" by two or more organizations concerning the procurement subjects, so in accordance with the stipulations of Article 93 of the Government Procurement Act, and Article 2 of the Regulations for The Implementation of Inter-entity Supply Contracts[5], an investigation of common requirements should be conducted first. However, this type of subject is prospective and profession-specific (innovative products or services in particular), and government organizations are generally not sure whether they have demand or not, which makes it difficult to reliably estimate the demand via the traditional demand survey method[6], resulting in a major obstacle for the procurement process. Therefore, the provisions are now revised to allow the Ministry of Economic Affairs to discuss procurement with each central government authority in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry, who consult or promote policies (such as the National Development Council, or central government authority in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry relevant to the procurement subjects), and then make decisions based on the quantities of goods and services of common requirements in accordance with the demand for promoting the policy. The provisions explicitly stipulate such flexibility in adopting methods other than the "traditional demand survey" method, as is required by laws for the common demand of Inter-entity Supply Contracts. Thus, agencies currently handling procurement of prospective or innovative subjects using inter-entity supply contracts, may reduce the administrative burden typically associated with conducting their own procurement. In addition, with a larger purchase quantity demand, as generated from two or more organizations, the process can more effectively inject momentum into the industry, and achieve a win-win situation for both supply and demand. (II)Government organizations may adopt "Priority Procurement" when handling procurement of innovative and green products or services. Prior to the amendment, the original provision of paragraph 2 of this Article stipulates that organizations may specify in the tender document Priority Procurement of certified green products; Additionally, a provision of paragraph 3 of the original Article stipulates that each central government authority in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry is authorized to establish the specifications, categories and other relevant matters of the green products[7] (according to the interpretation of the original text, it should include "Priority Procurement" in paragraph 3 of the Article).After the amendment of the Article, paragraph 2 of the original Article is moved to paragraph 4. In addition to the original green products, "innovative products or services" are included in the scope of "Priority Procurement" that organizations are permitted to adopt (but, the "software" in paragraph 1 was not included[8]). However, for organizations covered by The Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA), due to Taiwan's accession to the WTO, ANZTEC, and ASTEP, their procurement of items covered by the aforesaid agreements with a value reaching the stated threshold, shall be handled in accordance with the regulations stipulated in the aforesaid agreements; hence the stipulation in the proviso that the procurement must not violate the provisions in treaties or agreements ratified by the Taiwan government. Additionally, paragraph 3 of the original Article is moved to paragraph 5. Each central government authority in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry is authorized to use their own judgment on matters concerning the specifications, categories, certification processes of software, innovative and green products or services and the method for Priority Procurement of paragraph 4. In accordance with the authorization in paragraph 5 of the amended provision of this Article, each central government authority in charge of end enterprises of a specific industry may, depending on the specific policy requirement that promotes innovation development of its supervised industry, establish methods of identification and the processes of Priority Procurement for “Specific categories of innovative products or services", especially on products or services fitting the requirements of the method of using the demands of government organizations to stimulate industrial innovation. The established "Regolations for priority procurement of Specific categories of innovative products or services" is essentially a special regulation of the government procurement legislation, which belongs to the level of regulations, that is, it allows the organizations to apply measures other than the government procurement regulations and its related measures to the procurement process, and adopt "Preferential Contract Awarding" for qualified innovative products or services. Any government agency that has the need to procure a particular category of innovative product or service may, in accordance with the provisions of paragraph 4 of this Article, specify the use of Priority Procurement in the tender document, and administer the procurement, in accordance with the process of this particular category of innovative products, or priority procurement. The agency is now enabled to follow a more flexible procurement process than that of the government procurement regulations to more smoothly award contracts for qualified innovative products or services. Citing two examples of this applied scenario: Example one, "innovative information services": The central government authority in charge of information services is IDB. Thus, IDB may, according to the authorization provided for in paragraph 5 of the Article, establish the identification methods for innovative information services (the purpose of which is to define the categories and specifications of innovative services covered in the scope of priority procurement) and priority procurement processes, pertaining to emerging information services that are more applicable to the requirements of government agencies, such as: cloud computing services, IoT services, and Big Data analysis services.Example two, "Innovative construction or engineering methods": The central government authority in charge of construction affairs is the Construction and Planning Agency of the Ministry of the Interior. Since the agency has already established the "Guidelines for Approval of Applications for New Construction Techniques, Methods, Equipment and Materials", the agency may establish a priority procurement process for new construction techniques, methods or equipment, in accordance with the stipulations in paragraph 5 of the Article. Government agencies may conduct procurement following any of these priority procurement practices, if there is a requirement for innovative information services, or new construction techniques, methods or equipment. In addition to the two aforementioned flexible mechanisms for innovation procurement, where government agencies are granted flexible procedures to handle the procurement of innovative products or services via the use of the flexible procurement mechanism, paragraph 3, concerning the incentive measures of concessionary deductions, is added to the Article to reduce the bidding costs for tenderers participating in the tender. For the Procurement of software, innovative and green products or services encouraged by each central government authority in charge of end-enterprises of a specific industry (not limited to those handled by the authorities themselves, using inter-entity supply contracts or priority procurement methods), if the procurement subjects are still required to be tested, audited, accredited and certified by the government agencies, such a process falls under the scope of administrative fees collection, pursuant to paragraph 1 Article 7 of the Charges And Fees Act. However, considering that the item subject to test, audit, accreditation and certification may be in a trial or promotional period, or that it may be necessary to motivate tenderer participation, the provisions of paragraph 3 are thusly added to the Article to reduce, waive, or suspend the collection of aforementioned fees. Executive authorities in charge of collecting administrative fees shall proceed to reduce, waive, or suspend the collection pursuant to the stipulations of paragraph 3 of the Article and Article 12 subparagraph 7 of the Charges And Fees Act.[9] III.The direction of devising supporting measures of flexible mechanism for innovation procurement The latest amendment of the Statute for Industrial Innovation was promulgated and enacted on November 22, 2017, it is imperative that supporting measures pertaining to Article 27 of the Statute be formulated. As previously stated, the flexible mechanism for innovation procurement, as promoted in this Article, is designed specifically for the products or services that are pertinent to the government procurement requirements and are capable of stimulating industrial innovation, and providing a more flexible government procurement procedure for central authorities in charge of a specific industry as a policy approach in supporting industry innovation. Thus, the premise of devising relevant supporting measures is dependent on whether the specific industry, as overseen by the particular central authority, has a policy in place for promoting the development of industrial innovation, and on whether it is suitable in promoting the flexible mechanism for innovation procurement as described in this Article. The purpose of this Article is to promote the flexible mechanism for innovation procurement. Supporting measures pertaining to this Article will focus on the promotion of devising an "Innovation Identification Method", and of the "Priority Procurement Process" of the innovative products or services of each industry that central government authorities oversee. The former will rely on each central government authority in charge of a specific industry to charter an industry-appropriate and profession-specific planning scheme; while, for the latter, the designing of a priority procurement process, in accordance with the nature of the various types of innovative products or services, does not have to be applicable to all. However, regardless what type of innovative products or services the priority procurement process is designed for, the general direction of consideration should be given to - taking the different qualities of innovative products or services as the core consideration. Additionally, the attribute of the priority procurement procedures focusing specifically on the different qualities of the innovative subjects relates to the special regulation relevant to the government procurement regulations. Thus, the procurement procedures should follow the principle that if no applicable stipulation is found in the special regulation, the provisions of the principal regulation shall apply. The so-called "Priority Procurement" process refers to the "Preferential Contract Awarding" on tenders that meet certain criteria in a government procurement procedure. The existing Government Procurement Act (GPA, for short) and its related laws that have specific stipulations on "Priority Procurement" can be found in the "Regulations for Priority Procurement of Eco-Products" (Regulations for Eco-Products Procurement, for short), and the "Regulations for Obliged Purchasing Units / Institutions to Purchase the Products and Services Provided by Disabled Welfare Institutions, Organizations or Sheltered Workshops" (Regulations for Priority Procurement of Products or Services for Disabled or Shelters, for short). After studying these two measures, the priority procurement procedures applicable to criteria-conformed subjects can be summarized into the following two types: 1.The first type: Giving preferential contract awarding to the tenderer who qualifies with "the lowest tender price”, as proposed in the tender document, and who meets a certain criteria (for example, tenderers of environmental products, disabled welfare institutions, or sheltered workshops). There are two scenarios: When a general tenderer and the criteria-conformed tenderer both submit the lowest tender price, the criteria-conformed tenderer shall obtain the right to be the "preferential winning tender" without having to go through the Price Comparison and Reduction Procedures. Additionally, if the lowest tender price is submitted by a general tenderer, then the criteria-conformed tenderers have the right to a "preferential price reduction” option, that is, the criteria-conformed tenderers can be contacted, in ascending order of the tender submitted, with a one time option to reduce their bidding prices. The first tenderer who reduces their price to the lowest amount shall win the tender. Both the Regulations for Eco-Products Procurement[10] and Regulations for Priority Procurement of Products or Services for Disabilities or Shelters[11] have such relevant stipulations. 2.The second type: It is permitted to give Preferential Contract Awarding to a criteria-conformed tenderer, when the submitted tender is within the rate of price preference. When the lowest tenderer is a general tenderer, and the tender submitted by the criteria-conformed tenderer is higher than the lowest tender price, the law permits that if the tender submitted is "within the rate of price preference ", as set by the procuring entity, the procuring entity may award the contract preferentially to "the tender submitted by the criteria-conformed tenderer." The premise for allowing this method is that the tender submitted by the criteria-conformed tenderer must be within the preferential price ratio. If the submitted tender is higher than the preferential price ratio, then the criteria-conformed tenderer does not have the right to preferential contract awarding. The contract will be awarded to theother criteria-conformed tenderer, or to a general tenderer. This method is covered in the provisions of the Regulations for Eco-Products Procurement[12]. However, the important premise for the above two priority procurement methods is that the nature of the subject matter of the tender is suitable for adopting the awarding principle of the lowest tender (Article 52, Paragraph 1, Subparagraphs 1 and 2 of the Procurement Act), that is, it is difficult to apply these methods to the subjects if they are different qualities. Pursuant to the provisions of Article 66 of the Enforcement Rules of the Government Procurement Act, the so-called "different qualities" refers to the construction work, property or services provided by different suppliers that are different in technology, quality, function, performance, characteristics, commercial terms, etc. Subjects of different qualities are essentially difficult to compare when based on the same specifications. If just looking at pricing alone it is difficult to identify the advantages and disadvantages of the subjects, hence, the awarding principle of the lowest tender is not appropriate. The innovative subjects are essentially subjects of different qualities, and under the same consideration, they are not suitable for applying the awarding principle of the lowest tender. Therefore, it is difficult to adopt the lowest-tender-based priority procurement method for the procurement of innovative subjects. In the case of innovative subjects with different qualities, the principle of the most advantageous tender should be adopted (Article 52 Paragraph 1 Subparagraph 3 of the Procurement Act) to identify the most qualified vender of the subjects through open selection. Therefore, the procedure for the priority procurement of innovative subjects with different qualities should be based on the most advantageous tender principle with focus on the "innovativeness" of the subjects, and consideration on how to give priority to tenderers, who qualify with the criteria of innovation. Pursuant to the provisions of Article 56 Paragraph 4 of the Procurement Act, the Procurement and Public Construction Commission has established the "Regulations for Evaluation of the Most Advantageous Tender". The tendering authorities adopting the most advantageous tender principle should abide by the evaluation method and procedures delineated in the method, and conduct an open selection of a winning tender. According to the Regulations for Evaluation of the Most Advantageous Tender, in addition to pricing, the tenderers' technology, quality, function, management, commercial terms, past performance of contract fulfillment, financial planning, and other matters pertaining to procurement functions or effectiveness, maybe chosen as evaluation criteria and sub-criteria. According to the three evaluation methods delineated in the provisions of Article 11 of the Regulations for Evaluation of the Most Advantageous Tender (overall evaluation score method, price per score point method, and ranking method), pricing could not been included in the scoring. That is, "the prices of the subjects" is not the absolute criterion of evaluation of the most advantageous tender process. The priority procurement procedures designed specifically for innovative subjects with different qualities may adopt an evaluation method that excludes "pricing" as part of the scoring criterion so as to give innovative subject tenderers the opportunity to be more competitive in the bidding evaluation process, and due to the extent of their innovativeness, obtain the right to preferential tenders. If it must be included in the scoring, the percentage of the total score for pricing should be reduced from its usual ratio[13], while stipulating explicitly that "innovation" must be included as part of the evaluation criteria. In addition, its weight distribution should not be less than a ratio that highlights the importance of innovation in the evaluation criteria. Furthermore, when determining how to give preference to tenderers who meet certain innovation criteria in the contract awarding procedures, care should be taken to stay on focus with the degree of innovation of the subject (the higher the degree of innovation, the higher the priority), rather than giving priority to arbitrary standards. In summary, with consideration of priority procurement procedures designed specifically for innovative subjects with different qualities, this paper proposes the following preliminary regulatory directions: 1.Adopt the awarding principle of the most advantageous tender. 2.Explicitly stipulate the inclusion of "innovation" in the evaluation criteria and sub-criteria, and its ratio, one that indicates its importance, should not be less than a certain percentage of the total score (for example 20%). 3.Reduce the distributed ratio of "price" in the scoring criteria in the open selection. 4.After the members of the evaluation committee have concluded the scoring, if more than two tenderers have attained the same highest overall evaluated score or lowest quotient of price divided by overall evaluated score, or more than two tenderers have attained the first ranking, the contract is awarded preferentially to the tenderer who scores the highest in the "innovation" criterion. 5.When multiple awards (according to Article 52 Paragraph 1 Subparagraph 4 of the Procurement Act) are adopted, that is, there is more than one final winning tender, the procuring entity may select the tenderers with higher innovation scores as the price negotiation targets for contract awarding, when there are more than two tenderers with the same ranking. Using the above method to highlight the value of innovative subjects will make these suppliers more competitive, because of their innovativeness ratings in the procurement procedures, and not confine them to the limitation of price-determination. So that, subject suppliers with a high degree of innovation, may attain the right to the preferential contract awarding that they deserve due to their innovativeness, and the procuring entity can purchase suitable innovative products in a more efficient and easy process. It also lowers the threshold for tenderers with innovation energy to enter the government procurement market, thus achieving the goal of supporting industrial innovation and creating a win-win scenario for supply and demand. [1] Cross-reference Table of Amended Provisions of the Statute for Industrial Innovation, The Ministry of Economic Affairs, https://www.moea.gov.tw/MNS/populace/news/wHandNews_File.ashx?file_id=59099 (Last viewed date: 12/08/2017). [2] According to the Guidance for public authorities on Public Procurement of Innovation issued by the Procurement of Innovation Platform in 2015, the so-called innovation procurement in essence refers to that the public sector can obtain innovative products, services, or work by using the government procurement processes, or that the public sector can administer government procurement with a new-and-better process. Either way, the implementation of innovation procurement philosophy is an important link between government procurement, R & D and innovation, which shortens the distance between the foresighted emerging technologies/processes and the public sector/users. [3] The EU's innovative procurement mechanism comprises the "Public Procurement of Innovation Solutions" (PPI Solutions) and "Pre-Commercial Procurement" (PCP). The former is one of the government procurement procedures, explicitly regulated in the new EU Public Procurement Directive (Directive 2014/24 / EU), for procuring solutions that are innovative, near or in preliminary commercial prototype; The latter is a procurement process designed to assist the public sector in obtaining technological innovative solutions that are not yet in commercial prototype, must undergo research and development process, and are not within the scope of EU Public Procurement Directive. [4] The "software, innovative and green products or services", as described in paragraph 1 of Article 27 of the amended Statute for Industrial Innovation, refers to, respectively, "software", "innovative products or services", and "green products or services" in general. There is no co-ordination or subordination relationship between the three; the same applies to "innovative and green products or services" in paragraph 4. [5] Article 93 of the Government Procurement Act stipulates: "An entity may execute an inter-entity supply contract with a supplier for the supply of property or services that are commonly needed by entities." Additionally, Article 2 of the Regulations for The Implementation of Inter-entity Supply Contracts stipulates: "The term 'property or services that are commonly needed by entities' referred to in Article 93 of the Act means property or services which are commonly required by two or more entities. The term 'inter-entity supply contract (hereinafter referred to as the “Contract”)' referred to in Article 93 of the Act means that an entity, on behalf of two or more entities, signs a contract with a supplier for property or services that are commonly needed by entities, so that the entity and other entities to which the Contract applies can utilize the Contract to conduct procurements." Therefore, according to the interpretation made by the Public Construction Commission, the Executive Yuan (PCC, for short), organizations handling inter-entity supply contracts should first conduct a demand investigation. [6] In general, organizations in charge of handling the inter-entity supply contracts will disseminate official documents to applicable organizations with an invitation to furnish information online about their interests and estimated requirement (for budget estimation) at government's e-procurement website. However, in the case of more prospective subjects (such as cloud services of the emerging industry), it may be difficult for an organization to accurately estimate the demand when filling out the survey, resulting in a mismatch of data between the demand survey and actual needs. [7] In accordance with the authorization of paragraph 3 of the Article, the IDB has established "Regulations Governing Examination and Identification of Advanced Recycled Products by Ministry of Economic Affairs" (including an appendix: Identification Specification for Resource Regenerating Green Products), except that the priority procurement process was not stipulated, because the Resource Regenerating Green Products, that meet the requirements of the Ministry of Economic Affairs, are covered by the "Category III Products" in the provisions of Article 6 of the existing "Regulations for Priority Procurement of Eco-Products", set forth by the PPC and The Environmental Protection Administration of the Executive Yuan. Hence, organizations that have the requirement to procure green products, may proceed with priority procurement by following the regulations in the "Regulations for Priority Procurement of Eco-Products". [8] After the amendment of the Article, the "software" in the provisions of paragraph 1 was excluded in paragraph 4, because the objective of paragraph 4 is to promote industry innovation and sustainable development with the use of a more flexible government procurement procedure. Thus, the subjects of the priority procurement mechanism are focused on "innovative" and "green" products or services, which exclude popular "software" that has a common standard in the market. However, if it is an "innovative software", it may be included in the "innovative products or services" in the provisions of paragraph 4. [9] According to the provisions of Article 12 of the Charges And Fees Act: "In any of the following cases, the executive authority in charge of the concerned matters may waive or reduce the amount of the charges and fees, or suspend the collection of the charges and fees: 7. Waiver, reduction, or suspension made under other applicable laws." [10] Refer to Article 12, Paragraph 1, Subparagraphs 1 and Article 13, Paragraph 1 and 2 of Regulations for Priority Procurement of Eco-Products. [11] Refer to Article 4 of Regulations for Obliged Purchasing Units / Institutions to Purchase the Products and Services Provided by Disabled Welfare Institutions, Organizations or Sheltered Workshops. [12] Refer to Article 12, Paragraph 1, Subparagraphs 2 and Article 13, Paragraph 3 of Regulations for Priority Procurement of Eco-Products. [13] The provisions of paragraph 3 Article 16 of the Regulations for Evaluation of the Most Advantageous Tender stipulates: Where price is included in scoring, its proportion of the overall score shall be not less than 20% and not more than 50%.

Executive Yuan’s call to action:“Industrial Upgrading and Transformation Action Plan”I.Introduction Having sustained the negative repercussions following the global financial crisis of 2008, Taiwan’s average economic growth rate decreased from 4.4 percent (during 2000-2007 years) to 3 percent (2008-2012). This phenomenon highlighted the intrinsic problems the Taiwanese economic growth paradigm was facing, seen from the perspective of its development momentum and industrial framework: sluggish growth of the manufacturing industries and the weakening productivity of the service sector. Moreover, the bleak investment climate of the post-2008 era discouraged domestic investors injecting capital into the local economy, rendering a prolonged negative investment growth rate. To further exacerbation, the European Debt Crisis of 2011 – 2012 has impacted to such detriment of private investors and enterprises, that confidence and willingness to invest in the private sector were utterly disfavored. It can be observed that as Taiwan’s industrial core strength is largely concentrated within the the manufacturing sector, the service sector, on the other hand, dwindles. Similarly, the country’s manufacturing efforts have been largely centered upon the Information & Communications Technology (ICT) industry, where the norm of production has been the fulfillment of international orders in components manufacturing and Original Equipment Manufacturing (OEM). Additionally, the raising-up of society’s ecological awareness has further halted the development of the upstream petrochemical and metal industry. Consumer goods manufacturing growth impetus too has been stagnated. Against the backdrop of the aforementioned factors at play as well as the competitive pressure exerted on Taiwan by force of the rapid global and regional economic integration developments, plans to upgrade and transform the existing industrial framework, consequently, arises out as an necessary course of action by the state. Accordingly, Taiwan’s Executive Yuan approved and launched the “Industrial Upgrading and Transformation Action Plan”, on the 13th of October 2014, aiming to reform traditional industries, reinforcing core manufacturing capacities and fostering innovative enterprises, through the implementation of four principal strategies: Upgrading of Product Grade and Value, Establishment of Complete Supply Chain, Setting-up of System Integration Solutions Capability, Acceleration of Growth in the Innovative Sector. II.Current challenges confronting Taiwanese industries 1.Effective apportionment of industrial development funds Despite that Research and Development (R&D) funds takes up 3.02% of Taiwan’s national GDP, there has been a decrease of the country’s investment in industrial and technology research. Currently Taiwan’s research efforts have been directed mostly into manufacturing process improvement, as well as into the high-tech sector, however, traditional and service industries on the other hand are lacking in investments. If research funds for the last decade could be more efficiently distributed, enterprises would be equally encouraged to likewise invest in innovation research. However, it should be noted that Taiwan’s Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) based on their traditional developmental models, do not place research as their top priority. Unlike practices in countries such as Germany and Korea, the research fund input by private enterprises into academic and research institutions is still a relatively unfamiliar exercise in Taiwan. With regards to investment focus, the over-concentration in ICTs should be redirected to accommodate growth possibilities for other industries as well. It has been observed that research investments in the pharmaceutical and electric equipment manufacturing sector has increased, yet in order to not fall into the race-to-the-bottom trap for lowest of costs, enterprises should be continually encouraged to develop high-quality and innovative products and services that would stand out. 2.Human talent and labor force issues Taiwan’s labor force, age 15 to 64, will have reached its peak in 2015, after which will slowly decline. It has been estimated that in 2011 the working population would amount to a meager 55.8%. If by mathematical deduction, based on an annual growth rate of 3%, 4% and 5%, in the year 2020 the labor scarcity would increase from 379,000, 580,000 to 780,000 accordingly. Therefore, it is crucial that productivity must increase, otherwise labor shortage of the future will inevitably stagnate economic growth. Notwithstanding that Taiwan’s demographical changes have lead to a decrease in labor force; the unfavorable working conditions so far has induced skilled professionals to seek employment abroad. The aging society along with decrease in birth rates has further exacerbated the existing cul-de-sac in securing a robust workforce. In 1995 the employment rate under the age of 34 was 46.35%, yet in 2010 it dropped to a daunting 37.6%. 3.Proportional land-use and environmental concerns Taiwan’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is a time-consuming and often unpredictable process that has substantially deterred investor’s confidence. Additionally, there exists a disproportionate use of land resources in Taiwan, given that demand for its use predominantly stems from the northern and middle region of the country. Should the government choose to balance out the utilization of land resources across Taiwan through labor and tax policies, the situation may be corrected accordingly. III.Industrial Upgrading and Transformation Strategies The current action plan commences its implementation from October 2014 to end of December 2024. The expected industrial development outcomes are as follows: (1) Total output value of the manufacturing sector starting from 2013 at NTD 13.93 trillion is expected to grow in 2020 to NTD 19.46 trillion. (2) Total GDP of the service sector, starting at 3.03 trillion from 2011 is expected to grow in 2020 to 4.75 trillion NTD. 1.Strategy No.1 : Upgrading of product grade and value Given that Taiwan’s manufacturing industry’s rate for added value has been declining year after year, the industry should strive to evolve itself to be more qualitative and value-added oriented, starting from the development of high-end products, including accordingly high-value research efforts in harnessing essential technologies, in the metallic materials, screws and nuts manufacturing sector, aviation, petrochemical, textile and food industries etc. (1) Furtherance of quality research Through the employment of Technology Development Program (TDP) Organizations, Industrial TDP and Academic TDP, theme-based and pro-active Research and Development programs, along with other related secondary assistance measures, the industrial research capability will be expanded. The key is in targeting research in high-end products so that critical technology can be reaped as a result. (2) Facilitating the formation of research alliances with upper-, mid- and downstream enterprises Through the formation of research and development alliances, the localization of material and equipment supply is secured; hence resulting in national autonomy in production capacity. Furthermore, supply chain between industrial component makers and end-product manufacturers are to be conjoined and maintained. National enterprises too are to be pushed forth towards industrial research development, materializing the technical evolution of mid- and downstream industries. (3) Integrative development assistance in Testing and Certification The government will support integrative development in testing and certification, in an effort to boost national competitive advantage thorough benefitting from industrial clusters as well as strengthening value-added logistics services, including collaboration in related value-added services. (4) Establishment of international logistics centre Projection of high-value product and industrial cluster image, through the establishment of an international logistics centre. 2.Strategy No.2 : Establishment of a Complete Supply Chain The establishing a robust and comprehensive supply chain is has at its aim transforming national production capabilities to be sovereign and self-sustaining, without having to resort to intervention of foreign corporations. This is attained through the securing of key materials, components and equipments manufacturing capabilities. This strategy finds its application in the field of machine tool controllers, flat panel display materials, semiconductor devices (3D1C), high-end applications processor AP, solar cell materials, special alloys for the aviation industry, panel equipment, electric vehicle motors, power batteries, bicycle electronic speed controller (ESC), electrical silicon steel, robotics, etc. The main measures listed are as follows: (1) Review of industry gaps After comprehensive review of existing technology gaps depicted by industry, research and academic institutions, government, strategies are to be devised, so that foreign technology can be introduced, such as by way of cooperative ventures, in order to promote domestic autonomous development models. (2) Coordination of Research and Development unions – building-up of autonomous supply chain. Integrating mid- and downstream research and development unions in order to set up a uniform standard in equipment, components and materials in its functional specifications. (3) Application-theme-based research programs Through the release of public notice, industries are invited to submit research proposals focusing on specific areas, so that businesses are aided in developing their own research capabilities in core technologies and products. (4) Promotion of cross-industry cooperation to expand fields of mutual application Continuously expanding field of technical application and facilitating cross-industry cooperation; Taking advantage of international platform to induce cross-border technical collaboration. 3.Strategy No.3 : Setting-up of System Integration Solutions capability Expanding turnkey-factory and turnkey-project system integration capabilities, in order to increase and stimulate export growth; Combination of smart automation systems to strengthen hardware and software integration, hence, boosting system integration solution capacity, allowing stand-alone machinery to evolve into a total solution plant, thus creating additional fields of application and services, effectively expanding the value-chain. These type of transitions are to be seen in the following areas: turnkey-factory and turnkey-project exports, intelligent automated manufacturing, cloud industry, lifestyle (key example: U-Bike in Taipei City) industry, solar factory, wood-working machinery, machine tools, food/paper mills, rubber and plastic machines sector. Specific implementation measure s includes: (1) Listing of national export capability – using domestic market as test bed for future global business opportunities Overall listing of all national system integration capabilities and gaps and further assistance in building domestic “test beds” for system integration projects, so that in the future system-integration solutions can be exported abroad, especially to the emerging economies (including ASEAN, Mainland China) where business opportunities should be fully explored. The current action plan should simultaneously assist these national enterprises in their marketing efforts. (2) Formation of System Integration business alliances and Strengthening of export capability through creation of flagship team Formation of system integration business alliances, through the use of national equipment and technology, with an aim to comply with global market’s needs. Promotion of export of turnkey-factory and turnkey-projects, in order to make an entrance to the global high-value system integration market. Bolstering of international exchanges, allowing European and Asian banking experts assist Taiwanese enterprises in enhancing bids efforts. (3) Establishing of financial assistance schemes to help national enterprises in their overseas bidding efforts Cooperation with financial institutes creating financial support schemes in syndicated loans for overseas bidding, in order to assist national businesses in exporting their turnkey-factories and turnkey-solutions abroad. 4. Strategy No.4 : Acceleration of growth in the innovative sectors Given Taiwan economy’s over-dependence on the growth of the electronics industry, a new mainstream industry replacement should be developed. Moreover, the blur distinction between the manufacturing, service and other industries, presses Taiwan to develop cross-fields of application markets, so that the market opportunities of the future can be fully explored. Examples of these markets include: Smart Campus, Intelligent Transportation System, Smart Health, Smart City, B4G/5G Communications, Strategic Service Industries, Next-Generation Semiconductors, Next-Generation Visual Display, 3D Printing, New Drugs and Medical Instruments, Smart Entertainment, Lifestyle industry (for instance the combination of plan factory and leisure tourism), offshore wind power plant, digital content (including digital learning), deep sea water. Concrete measures include: (1) Promotion of cooperation between enterprises and research institutions to increase efficiency in the functioning of the national innovation process Fostering of Industry-academic cooperation, combining pioneering academic research results with efficient production capability; Cultivation of key technology, accumulation of core intellectual property, strengthening integration of industrial technology and its market application, as well as, establishment of circulation integration platform and operational model for intellectual property. (2) Creating the ideal Ecosystem for innovation industries Strategic planning of demo site, constructing an ideal habitat for the flourishing of innovation industries, as well as the inland solution capability. Promotion of international-level testing environment, helping domestic industries to be integrated with overseas markets and urging the development of new business models through open competition. Encouraging international cooperation efforts, connecting domestic technological innovation capacities with industries abroad. (3) Integration of Cross-Branch Advisory Resources and Deregulation to further support Industrial Development Cross-administrations consultations further deregulation to support an ideal industrial development environment and overcoming traditional cross-branch developmental limitations in an effort to develop innovation industries. IV. Conclusion Taiwan is currently at a pivotal stage in upgrading its industry, the role of the government will be clearly evidenced by its efforts in promoting cross-branch/cross-fields cooperation, establishing a industrial-academic cooperation platform. Simultaneously, the implementation of land, human resources, fiscal, financial and environmental policies will be adopted to further improve the investment ambient, so that Taiwan’s businesses, research institutions and the government could all come together, endeavoring to help Taiwan breakthrough its currently economic impasse through a thorough industrial upgrading. Moreover, it can be argued that the real essence of the present action plan lies in the urge to transform Taiwan’s traditional industries into incubation centers for innovative products and services. With the rapid evolution of ICTs, accelerating development and popular use of Big Data and the Internet of Things, traditional industries can no longer afford to overlook its relation with these technologies and the emerging industries that are backed by them. It is only through the close and intimate interconnection between these two industries that Taiwan’s economy would eventually get the opportunity to discard its outdated growth model based on “quantity” and “cost”. It is believed that the aforementioned interaction is an imperative that would allow Taiwanese industries to redefine its own value amidst fierce global market competition. The principal efforts by the Taiwanese government are in nurturing such a dialogue to occur with the necessary platform, as well as financial and human resources. An illustration of the aforementioned vision can be seen from the “Industrie 4.0” project lead by Germany – the development of intelligent manufacturing, through close government, business and academic cooperation, combining the internet of things development, creating promising business opportunities of the Smart Manufacturing and Services market. This is the direction that Taiwan should be leading itself too. References 1.Executive Yuan, Republic of China http://www.ey.gov.tw/en/(last visited: 2015.02.06) 2.Industrial Development Bureau, Ministry of Economic Affairs http://www.moeaidb.gov.tw/(last visited: 2015.02.06) 3.Industrial Upgrading and Transformation Action Plan http://www.moeaidb.gov.tw/external/ctlr?PRO=filepath.DownloadFile&f=policy&t=f&id=4024(last visited: 2015.02.06)